1. The Economics: Why Tea for Horses?

The trade was driven by a nutrient gap. In the high altitudes of Tibet, vegetables do not grow well. The diet consists of yak meat, dairy, and barley (tsampa). Without a source of Vitamin C and polyphenols, the population suffered from malnutrition and digestion issues.

Tea acted as a "vegetable substitute," helping digest the heavy fats of yak butter. Meanwhile, the Chinese Song and Tang dynasties were in constant warfare with northern nomads. They lacked sturdy horses. The solution was a government-controlled barter system: Tea Horse Agencies were established to regulate the exchange.

Expert Tip: Butter Tea (Po Cha)

The tea transported wasn't drunk like we drink it today. Tibetans boiled the tea bricks for hours, then churned the dark liquid with yak butter and salt. This high-calorie soup (Po Cha) provided the energy needed to survive the freezing climate.

2. The Route: The World's Most Dangerous Path

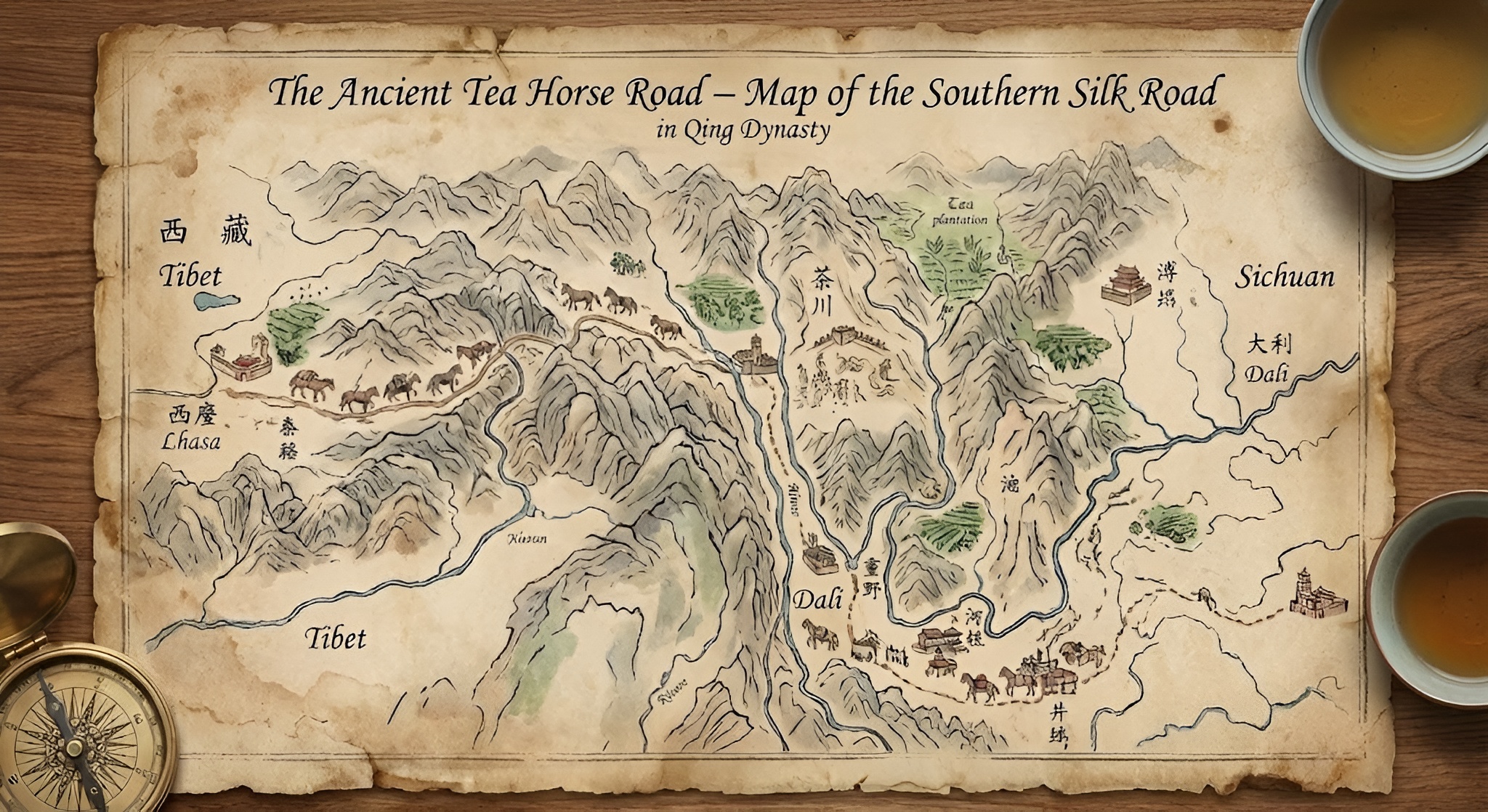

The Tea Horse Road was not a single paved road, but a web of caravan trails stretching over 2,000 miles. It wound through the Hengduan Mountains—a geological nightmare of deep gorges and soaring peaks.

| Route Section | Origin | Terrain | Tea Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yunnan Route | Pu'er / Xishuangbanna | Tropical jungles to snowy passes. | Large Leaf Pu-erh (Sheng) |

| Sichuan Route | Ya'an | Steep cliffs, wet and foggy. | Dark Tea (Hei Cha / Zang Cha) |

Expert Tip: Why Bricks?

Loose leaf tea is bulky and fragile. To transport it efficiently, tea was steamed and compressed into solid bricks or cakes. This increased the density, allowing a porter to carry more value per trip, and protected the tea from physical damage.

3. The Accidental Invention of Aged Tea

When the tea left Yunnan, it was essentially a green tea (Sun-Dried Maocha). However, the journey to Lhasa took 3 to 6 months.

During this time, the tea bricks were exposed to high humidity, rain, and the body heat of the pack animals. This environment triggered post-fermentation. Microbes and enzymes broke down the harsh tannins, turning the tea dark, smooth, and earthy. By the time it arrived in Tibet, it had transformed into what we now recognize as Aged Pu-erh or Dark Tea (Hei Cha).

Expert Tip: Recreating the Journey

Modern "Wet storage" or "Traditional Storage" techniques in Hong Kong warehouses mimic the humid conditions of the Tea Horse Road to speed up the aging of Pu-erh. Without this humidity, the tea ages much slower (Dry Storage). Learn more in our Pumidor Guide.

4. The Human Cost: The Porters

While horses were the commodity, humans were often the engine. In the Sichuan sections, the paths were often too narrow or steep for laden animals. Men and women (known as "Bei Fu") carried the tea.

A standard load was 60-70kg, but strong porters could carry up to 90kg—more than their own body weight. They used T-shaped walking sticks to rest the heavy load on the steep steps without putting it down.

Expert Tip: The End of the Road

The Tea Horse Road remained active until World War II, when it became a vital supply line for the Allies fighting the Japanese. By the 1950s, modern highways and trucks finally replaced the caravans, ending a millennium of tradition.

Summary: The Trade by Numbers

| Metric | Statistic |

|---|---|

| Duration | Approx. 6th Century to 1950s |

| Length | ~2,400 Miles (4,000 km) |

| Volume | Millions of kg of tea annually at peak |

| Commodity | Pu-erh (Yunnan) & Zang Cha (Sichuan) |

Want to taste history?

You can still buy tea cakes that are pressed and aged in the traditional style. To start your journey into fermented tea, read our beginner's guide: What is Hei Cha (Dark Tea)? The Ancient Fermented Brew →

Comments