1. Why Prune Tea: Yield vs. Wild Growth Comparison

Unpruned tea plant growth: Wild tea trees = 5-15 meter height (natural tree form—Camellia sinensis var. assamica especially tall, ancient Yunnan specimens 20+ meters), energy diverted to vertical growth (trunk/branches develop—not productive shoots, low harvestable leaf density per bush volume), picking impossible (new shoots at canopy top—ladder required, commercial impractical). Yields from unpruned bush: 50-100g annually (scattered tall shoots—inaccessible + inefficient, novelty only not production). Wild tree harvesting (ancient puerh trees—specialty market, but requires climbing equipment + selective picking, see wild puerh economics).

Pruned bush advantages: Compact height (40-80cm productive layer—comfortable picking without bending/ladders, ergonomic harvesting), dense lateral branching (pruning triggers dormant buds—creates 5-10× more shoots than unpruned, concentrated productivity), uniform maturity (flat top canopy—shoots receive equal light, flush together for efficient harvest timing), extended productive life (managed bushes produce 50+ years—vs. unpruned plants declining after 20 years as canopy becomes inaccessible). Yield transformation: Properly pruned mature bush (year 5+) = 300-800g annually (vs. 50-100g unpruned—5-8× productivity increase, justifies pruning labor investment).

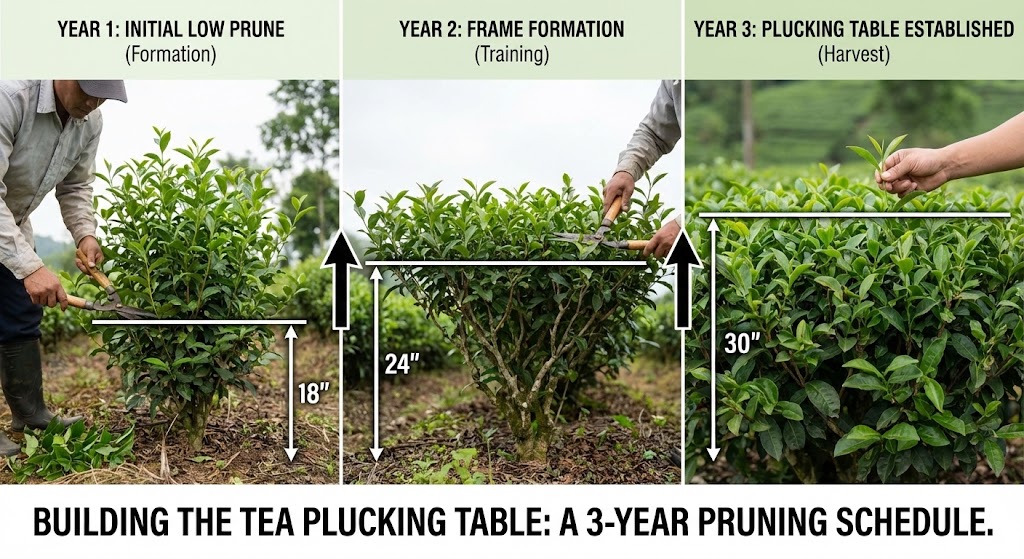

2. The 3-Year Pruning Cycle: Establishing Structure

Year 1 (planting year): NO pruning, NO harvest (establishment priority—root system development critical, any pruning/picking diverts energy from roots), exception: tip pinching (if single-stem seedling reaches 30cm—pinch top 2cm to force branching, encourages bushy form vs. single trunk, one-time intervention only). Fertilization focus (monthly growing season—nitrogen-rich ericaceous feed, see container feeding or soil nutrition), height expectation (30-50cm by end year 1—healthy plant, shorter = insufficient light/nutrients investigate conditions).

Year 2 (first structural prune): Early spring pruning (March-April before bud break—plant dormant, pruning stimulates vigorous regrowth), hard prune to 20-30cm (cut back all growth—seems drastic but essential, forces dense basal branching creating bush framework), use sharp secateurs (clean cuts—sterilize with alcohol between cuts prevents disease spread), cut at 45° angle (sheds water—prevents rot at cut site, slopes away from bud). Summer response: 5-8 strong shoots emerge (lateral bud activation—creating multi-stem bush structure, select 4-6 strongest allow development remove weak shoots), light harvest acceptable (late summer once shoots mature—one gentle picking 30-50g, don't over-harvest allows continued establishment).

Year 3 (Banji formation begins): Spring maintenance prune (March-April—trim uneven shoots to create flat horizontal surface 40-50cm height, this is initial "plucking table" or Banji level), harvest at consistent height (every flush thereafter—pluck 2 leaves + bud at Banji level, never vary up or down, consistency critical for dense productive layer formation), mid-summer light prune (July—remove any vertical shoots breaking through Banji, maintain flat-top discipline). Yield year 3: 100-200g (bush transitioning to production—Banji forming, 3-4 flushes achievable in temperate climate see flush timing).

Optimal Banji Height Selection

Consider your picking comfort: Low Banji (30-40cm) = Maximum vegetative vigor (closer to roots—more energy for regrowth, faster flush intervals), but requires sitting/kneeling to harvest (back strain—uncomfortable for extended picking sessions). Medium Banji (40-60cm) = Best compromise (standing harvest with slight bend—comfortable for most people, good vigor + accessibility balance), recommended for home growers. High Banji (60-80cm) = Easiest picking (stand upright—minimal bending, ideal for those with back issues), but reduced vigor (further from root energy—slightly slower regrowth, acceptable trade-off for ergonomics). Once established, don't change height (maintain exact level—Banji density depends on consistency, shifting up/down creates gaps in productive layer).

3. Year 4+ Maintenance Pruning: Sustaining Productivity

Annual light pruning (spring): Remove dead/damaged wood (winter die-back in cold climates—prune to green tissue, prevents disease harboring in dead stems), thin crossing branches (interior congestion—remove branches rubbing/shading each other, improves air circulation reduces fungal disease), maintain Banji level (trim any shoots significantly above/below plane—preserves flat-top uniformity). Timing: Early spring before bud break (March in UK—plant still dormant, pruning wounds heal quickly as growth begins), avoid autumn pruning (stimulates new growth—vulnerable to winter damage, any necessary corrective work do spring only).

Summer "skiffing" (optional intensive management): What is skiffing: Mechanical hedge-trimmer style pruning (commercial estates—motorized shear across Banji surface, levels entire field section rapidly), home adaptation (manual hedge shears—trim entire bush to exact Banji height mid-season, removes over-mature shoots + forces uniform new flush). Timing: Mid-July after second flush harvest (allows 6-8 weeks regrowth—produces autumn flush, resets bush for next season). Benefits: Uniform flush timing (all shoots same age—harvest efficiency maximized), rejuvenating effect (removes accumulated old wood—stimulates vigorous young growth), weed suppression (dense canopy shades soil—reduces weeding labor). Disadvantages: Sacrifices one potential flush (July-August harvest lost—recovering from skiff, only viable if enough other flushes compensate).

Every 3-5 years: Rejuvenation hard prune: Why necessary: Banji gradually thickens with woody growth (accumulated stems from years of cutting—reduces new shoot space, productivity declines 10-20% vs. peak), solution = reset cycle (hard prune back to 15-20cm—removes old framework, forces basal regrowth creating fresh productive structure). Timing: Early spring year 6, 9, 12 etc. (every 3-year intervals commercial standard—home growers flexible based on bush vigor observation, if flush density declining = time for rejuvenation). Sacrifice year: Minimal harvest during regrowth (allow plant rebuild—light picking only after new structure established, full production resumes year following hard prune). Long-term benefit: Extends productive life indefinitely (50+ year bushes maintained via cyclical rejuvenation—vs. gradual decline without intervention).

| Bush Age | Pruning Action | Timing | Purpose | Harvest Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year 1 | None (optional tip pinch) | If needed: summer | Root establishment, branching start | NO HARVEST |

| Year 2 | Hard prune to 20-30cm | Early spring (March-April) | Force bushy structure, lateral branching | Light harvest late summer (30-50g) |

| Year 3 | Establish Banji 40-50cm | Spring shape + maintain via harvesting | Create plucking table, uniform growth plane | Moderate harvest (100-200g) |

| Year 4-5 | Light annual maintenance | Spring (dead wood removal) | Sustain Banji, remove damaged growth | Full production (300-500g) |

| Year 6, 9, 12... | Rejuvenation hard prune (15-20cm) | Early spring (3-year cycle) | Remove old wood, reset productivity | Minimal during recovery year |

4. Pruning Techniques: Cuts, Angles, and Tool Selection

Tool requirements: Bypass secateurs (sharp scissor-action—clean cuts not crushing, Felco/ARS brands professional standard £30-60), avoid anvil pruners (crushing action—damages stem tissue, promotes disease entry), hedge shears for skiffing (manual long-blade—levels Banji surface, or electric hedge trimmer for large bushes >10 plants). Maintenance critical: Sharpen before each season (dull blades tear stems—ragged wounds invite infection, whetstone or professional sharpening service), sterilize between cuts (70% isopropyl alcohol or 10% bleach solution—prevents disease transmission, especially if any diseased material encountered).

Cut angle and positioning: 45° angle sloping away from bud (water sheds off—prevents pooling in cut, reduces rot risk), 5mm above bud (close enough to heal—but not damaging bud itself, too far leaves stub that dies back), identify outward-facing bud (cut above bud pointing away from bush center—encourages open growth habit, inward buds create congested interior). Avoid flush cuts (cutting exactly at branch collar—damages trunk tissue, 5mm stub acceptable for tea vs. ornamental pruning standards), clean single motion (don't saw/twist—smooth cut heals fastest, hesitation creates ragged edge).

Seasonal timing importance: Dormant season (winter) best (November-February in temperate zones—plant not actively growing, pruning stress minimized, wounds seal before spring growth), early spring acceptable (March-April—just before bud break, pruning stimulates vigorous flush from cuts), AVOID late spring/summer major pruning (May-August—actively growing, pruning diverts energy from production, wounds don't heal as cleanly in heat). Exception: Light corrective pruning + harvest anytime (removing single shoots—minimal stress, different from structural pruning which waits for dormancy).

5. Training Young Plants: Single Stem to Bush Form

Seedling growth pattern: Natural tendency = single trunk (apical dominance—terminal bud suppresses lateral branching, grows vertically like small tree), unsuitable for harvest (year 2-3 = 60-80cm single stem with few side shoots—picking impractical). Intervention required (break apical dominance—force lateral bud activation, create multi-stem bush architecture). Cutting-grown plants (propagated from cuttings see propagation methods—often naturally bushier, but may still need training if from vigorous upright cutting).

Tip pinching protocol (year 1 method): When to pinch: Seedling reaches 25-30cm height (usually 4-6 months from germination—adequate root system established, can support branching energy demand), how to pinch (fingernails or scissors—remove top 2-3cm including apical bud, leaves 20-25cm stem with 6-8 leaves below), result (2-4 weeks later—multiple side shoots emerge from leaf axils below pinch point, transforms single stem into multi-branch form). Repeat if necessary: If new shoots grow vertically (single dominant leader re-emerges—pinch again at 30cm, some vigorous seedlings require 2-3 pinches to establish bushy habit).

Year 2 hard prune (definitive training): Regardless of year 1 pinching (all plants get year 2 hard prune—ensures proper framework), cut to 20-30cm from ground (removes all top growth—seems harsh but forces strong basal branching creating 4-8 new stems from base), post-prune care (fertilize monthly—support vigorous regrowth, mulch to conserve moisture, remove weak shoots in summer leaving 4-6 strongest for framework). This prune sets bush architecture (following years just maintain height—fundamental structure created now, determines productive capacity for plant's lifetime).

6. Rejuvenating Neglected/Overgrown Bushes

Identifying neglected bush: Symptoms = Overgrown height (1.5+ meters—unpruned for 5+ years, canopy beyond comfortable reach), sparse Banji (if ever had one—now degraded with gaps, woody stems dominate vs. productive shoots), declining yields (old wood accumulation—fewer new shoots per area, harvests diminishing annually), dead wood throughout (disease/winter damage—unpruned plants self-thin poorly). Common scenario: Inherited mature plant (previous owner didn't harvest—just ornamental camellia relative, or abandoned tea project resuming years later).

Rejuvenation hard prune (drastic but effective): Timing = Early spring (March-April—dormant or just breaking dormancy, maximizes recovery time before next winter), severity = Cut entire bush to 15-25cm from ground (removes 80-90% of plant—shocking but necessary, tea tolerates this well unlike some species that die from hard pruning), technique (saw for thick stems >2cm diameter—secateurs insufficient, clean cuts not ragged tears). Immediate aftermath: Looks like brown stump (aesthetically concerning—but hidden buds along stems + basal area activate within 4-6 weeks, green shoots emerge vigorously).

Recovery timeline and management: Weeks 4-8 (multiple new shoots emerge—10-20+ from various points on old wood, select 6-10 strongest for new framework remove weak ones), summer year 1 (new shoots reach 30-50cm—allow growth no harvest, fertilize monthly support recovery), spring year 2 (prune to establish Banji at 40-50cm—creating productive layer, now following standard year 3 protocol see earlier section), year 2-3 post-rejuvenation (resume normal harvesting—bush fully restored, productivity exceeds pre-pruning levels due to renewed vigor). Success rate high (90%+ plants recover—tea extremely resilient, failures usually due to root disease not pruning trauma).

7. Troubleshooting Pruning Problems

Problem: Weak regrowth after hard prune: Causes = Root system compromised (disease/waterlogging—insufficient root mass to support top regrowth, check for root rot brown mushy roots vs. healthy white), nutrient deficiency (depleted soil—can't fuel vigorous shoots, see fertilization needs), wrong timing (late summer prune—insufficient recovery time before winter dormancy). Solutions: Root inspection (carefully excavate root zone—look for rot/damage, improve drainage if soggy soil identified), heavy fertilization (high-nitrogen feed—weekly dilute applications vs. monthly, boosts shoot vigor), patience (some bushes slow responders—may take 8-12 weeks vs. typical 4-6, eventually activate). Failure diagnosis: If zero new growth by 12 weeks (plant likely dead—scratch stem reveals brown dry tissue not green, start replacement plant).

Problem: Uneven Banji formation (irregular surface): Causes = Inconsistent harvest height (varied plucking—some areas cut higher others lower, creates bumpy surface), uneven sun exposure (shaded side slower growth—south side vigorous north side sparse), pest damage (localized aphid infestation—stunts shoots one area while rest thrives). Solutions: Corrective leveling prune (trim high areas down to desired Banji plane—sacrifices flush from those sections but creates uniformity, recovers within one growing cycle), disciplined harvest height (use visual marker like bamboo stake at Banji level—ensures consistent cutting, train eye to recognize exact height without measuring), improve light uniformity (prune overhanging trees—or accept north side will be less productive, rotate container plants weekly if pot-grown). Timeline to uniformity: 2-3 seasons strict discipline (gradual convergence—patience + consistency yields professional flat-top appearance).

Problem: Bush declining despite regular pruning: Causes = Over-harvesting (picking too frequently—exhausting plant faster than recovery, see harvest frequency limits), soil depletion (years without fertilization—container tea especially vulnerable, nutrients finite in pots see container soil maintenance), disease (root rot/blister blight—progressive weakening despite good pruning practice), soil pH shift (alkaline creep from tap water—locks nutrients even if present, see acidity management). Solutions: Rest year (minimal harvest 1 season—allows plant rebuild reserves, resume normal picking when vigor restored), soil test + amendment (pH check—adjust to 4.5-5.5 if drifted, add compost + fertilizer replenish nutrients), disease diagnosis (inspect leaves/roots for fungal symptoms—treat with appropriate fungicide or improve air circulation + drainage). Rejuvenation hard prune (if decline continues—year 15-20 old bush may just need reset, hard prune often cures mysterious decline by forcing fresh growth).

Comments