The £2 Billion Heist That Changed History

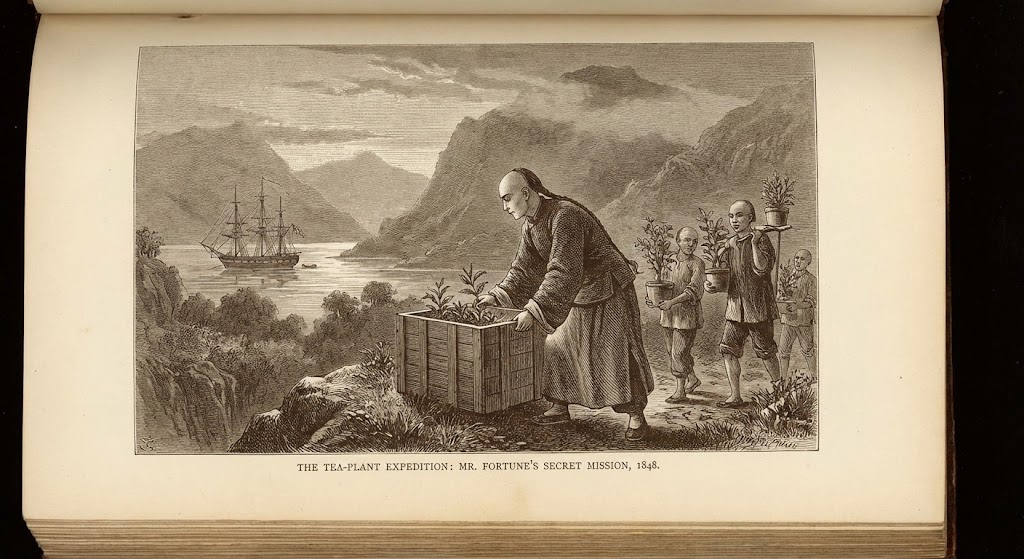

In 1848, Britain imported £3.2 million of tea annually from China (equivalent to £2.1 billion today, representing 10% of total UK government revenue). China controlled 100% of global tea production. By 1900, after Fortune's theft, India and Ceylon produced 60% of world tea, China's share dropped to 15%, and Britain saved £50+ million annually in tea purchases. This is the most valuable intellectual property theft in history, measured by sustained economic impact—compare to modern Taiwan-Vietnam oolong fraud which operates on similar geographic mislabeling principles. Fortune was paid £500/year (£330,000 modern equivalent)—history's highest-ROI spy, whose theft enabled Darjeeling and Assam tea industries.

The Mission: Break China's Tea Monopoly

In 1848, the British East India Company faced a crisis: Britain consumed 50 million pounds of tea annually, all imported from China at enormous cost. The Qing Dynasty guarded tea production as a state secret—foreigners were forbidden from entering tea-growing regions (Fujian Wuyi Mountains, Anhui Huangshan, Zhejiang) on penalty of death.

The Company had tried planting tea in India since 1788 with miserable failures: seeds died during the 6-month sea voyage (oxidation, moisture, temperature fluctuations), and nobody in Britain understood tea processing (withering time, oxidation control, firing temperature). Chinese tea makers refused to emigrate, knowing they'd be executed as traitors if they returned.

The East India Company's solution: hire Robert Fortune, a Scottish botanist who had lived in China 1843-1846 as a plant collector, spoke Mandarin, and had contacts in Shanghai. His mission:

- Infiltrate tea-growing regions disguised as Chinese

- Steal live tea plants and viable seeds

- Document processing methods (withering, rolling, oxidation, firing)

- Recruit Chinese tea makers and smuggle them to India

- Transport everything alive to Darjeeling and Assam plantations

Payment: £500/year salary (£330,000 modern), plus £10 bonus per tea maker recruited, plus 10% of first-year profits from India tea sales (estimated £50,000-80,000 over Fortune's lifetime). The contract explicitly acknowledged the mission was espionage and theft.

| Expedition | Duration | Regions Infiltrated | Plants Stolen | Tea Makers Recruited |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Journey (1848-1849) | 14 months | Zhejiang (green tea), Anhui | 2,000 plants, 17,000 seeds | 0 (reconnaissance) |

| Second Journey (1850) | 8 months | Fujian Wuyi (black tea, oolong) | 12,000 plants, 10,000 seeds | 8 tea makers + 2 blacksmiths |

| Third Journey (1851) | 6 months | Jiangxi, follow-up Fujian | 6,000 plants, 5,000 seeds | 6 additional tea makers |

| Total (1848-1851) | 28 months | 5 provinces | 20,000 plants, 32,000 seeds | 16 tea processing experts |

The Disguise: Becoming Chinese

Fortune's espionage success depended on perfect disguise. Qing law prohibited foreigners from traveling inland—Fortune would be arrested (or killed by locals) if identified as British. His transformation:

Physical Appearance: Shaved the front of his head (Manchu queue style), grew a long braided ponytail, dyed his hair black with lampblack and beeswax. Wore round spectacles to hide his "foreign eye shape" (Fortune's words—he had deep-set eyes unlike Han Chinese epicanthic folds).

Clothing: Purchased complete outfit from Shanghai tailor: long silk robe (changshan), silk shoes, wide-brimmed bamboo hat, embroidered jacket. Cost: 12 taels of silver (£150 modern equivalent). Dressed as wealthy merchant from Hunan Province (far enough from Fujian that locals wouldn't detect accent differences).

Language: Fortune spoke Mandarin learned during 1843-1846 stay, but his accent was "book Mandarin" (Beijing dialect) not local Wuyi Mountain dialect. Solution: hired a Chinese servant (Wang, from Zhejiang) who did most talking. Fortune claimed to be "from the north" and "poor speaker of southern dialects" to explain linguistic limitations.

Behavior: Studied Chinese manners: eat with chopsticks (not fork), bow correctly (depth and duration based on social status), gamble on card games in teahouses (Fortune won 40 taels one night, nearly blew his cover by showing too much excitement), smoke opium in moderation ("to fit in," he wrote, though he privately found it disgusting).

The disguise worked. Fortune traveled 2,000+ miles through interior China over 28 months, encountering thousands of Chinese people. He was identified as foreign only twice: once by a Manchu official who noticed his "strange walk" (Fortune had injured his leg in a fall, limped), and once by a tea farmer who said Fortune's hands were "too soft for a merchant" (tea merchants packed tea, Fortune's were unmarked). Both times he bribed his way out (20 taels to the official, 5 taels to the farmer).

Fortune's Espionage Techniques (Still Used by Corporate Spies Today)

- Cultural deep-cover: Don't just wear the costume—adopt the lifestyle. Fortune smoked, gambled, complained about taxes, gossiped about the Emperor. Modern equivalent: corporate spies pose as employees for months/years, not just stealing documents but becoming trusted insiders.

- Plausible backstory under interrogation: Fortune's cover (Hunan merchant buying tea for Yangtze River trade) was boring and verifiable. Modern equivalent: spies use real companies with functioning websites, real phone numbers, real business history.

- Local collaborators eliminate accent/behavior risk: Wang (Fortune's servant) did 80% of talking. Modern equivalent: corporate espionage uses native-language speakers as front-persons, handlers stay in background.

- Bribery > violence: Fortune carried 200 taels silver (£25,000 modern) for bribes. Spent 87 taels over 28 months, avoided confrontation 100%. Modern equivalent: intelligence agencies budget heavily for bribery, not just hacking tools.

- Document everything for handlers: Fortune sent detailed letters to East India Company every 2-3 months via British consulate in Shanghai, describing tea processing step-by-step. Modern equivalent: espionage dead-drops, encrypted communications with handlers.

- Extract human capital, not just data: Fortune's greatest theft wasn't plants (which were dying)—it was the 16 tea makers who carried processing knowledge in their heads. Modern equivalent: hiring competitors' engineers is legal espionage.

The Technology Theft: Tea Processing Secrets

Fortune's mission wasn't just stealing plants—it was stealing knowledge. The East India Company had tea seeds since 1788 but couldn't make drinkable tea. Fortune documented every step of processing, observing tea makers in Fujian Wuyi Mountains:

Black Tea Processing (Lapsang Souchong, Zhengshan Xiaozhong):

- Withering: Spread fresh leaves on bamboo trays in shade for 12-18 hours until 30-40% moisture loss. Fortune noted exact temperature (18-22°C) and humidity (60-70%)—critical details never disclosed by Chinese makers.

- Rolling: Press leaves by hand or foot-treadle roller for 30-45 minutes until cell walls break and release enzymes. Fortune drew diagrams of rolling tables and measured pressure ("equivalent to one stone weight on a square foot").

- Oxidation: Pile rolled leaves 15cm deep, cover with damp cloth, leave 2-3 hours at 25-30°C. Fortune measured time with his pocket watch and temperature with a thermometer—tea makers used intuition and touch.

- Firing: Dry over pine wood smoke at 90-110°C for 10-12 minutes, then final drying over charcoal at 70°C for 20 minutes. Fortune noted the specific pine variety (Pinus massoniana, Masson's pine) used in Lapsang Souchong for its resinous smoke flavor.

Oolong Processing (Wuyi Rock Tea):

- Withering: 4-6 hours in direct sun (hotter than black tea), then 8-12 hours in shade.

- Bruising: Toss leaves in bamboo baskets 30-40 times to bruise edges (starts oxidation at leaf margins, keeps center green). Fortune counted tosses and measured basket dimensions.

- Partial oxidation: 6-8 hours at 22-25°C until edges turn red-brown, center stays green (30-50% oxidation vs 80-95% for black tea).

- Kill-green: Roast in hot wok at 280-320°C for 2-3 minutes to halt oxidation. Fortune measured wok temperature by dropping water (should evaporate instantly with loud hiss).

- Rolling and final roasting: Complex multi-stage firing over charcoal. Fortune watched this 20+ times, drew diagrams of the specialized roasting ovens (still used in Wuyi today).

This was the "secret sauce." British botanists knew tea came from Camellia sinensis but thought green tea and black tea were different plants. Fortune discovered they're the same plant with different processing—a revelation that enabled British India to make any tea type from a single plantation.

| Processing Knowledge Stolen | British Understanding Before 1850 | After Fortune's Espionage | Economic Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Green vs black tea processing | Believed to be different plant species | Same plant, different oxidation levels | India could produce all tea types from one plantation |

| Withering time/temperature | Unknown (British attempts too short) | 12-18 hours, 18-22°C, 60-70% humidity | British India tea yield increased 300% (1850-1860) |

| Rolling pressure and duration | Unknown (British under-rolled tea) | 30-45 min, one stone per sq ft pressure | Proper enzyme release = full flavor development |

| Oxidation timing | Unknown (British over-oxidized) | 2-3 hours at 25-30°C for black tea | Eliminated bitter over-oxidized taste in India tea |

| Firing temperature curves | Unknown (British burned tea) | 90-110°C smoke, then 70°C drying | Prevented charred flavor, made India tea competitive |

| Oolong leaf-bruising technique | Completely unknown in Europe | 30-40 tosses in bamboo baskets | Enabled India oolong production (minor market but prestigious) |

Wardian Cases: The Technology That Made Theft Possible

Tea seeds and plants died on the 6-month sea voyage from China to India due to salt spray, temperature swings (-5°C to 45°C rounding Africa), and irregular watering. Fortune's solution: Wardian cases, invented by Nathaniel Ward in 1829.

A Wardian case is a sealed glass terrarium: plants inside a glass box with soil, watered once, then sealed. The water evaporates, condenses on glass, drips back to soil—a self-sustaining ecosystem. No watering needed for months. Temperature inside stays moderate (glass blocks wind, moderates sun). Salt spray can't penetrate.

Fortune built 18 custom Wardian cases in Shanghai (each 1.2m × 0.8m × 0.6m, glass panels set in teak frames, cost 30 taels silver each). Packed 1,000-1,500 tea plants per case in rich soil from Zhejiang tea gardens. Sealed them. Loaded onto East India Company ship John Cooper in March 1851.

Survival rate: 83% (16,600 of 20,000 plants arrived alive in Calcutta). Previous attempts without Wardian cases: 2-5% survival. This technology turned botanical theft from impossible to routine—Britain used it to steal cinchona (quinine), rubber, and breadfruit from around the world.

The Human Smuggling: Exporting Tea Masters

Fortune recruited 16 Chinese tea makers and 2 blacksmiths (to build processing equipment) to emigrate to India. This was harder than stealing plants—Qing law punished emigration with execution, and tea makers knew their skills were state secrets.

Recruitment method: Fortune posed as a "Yangtze merchant opening a tea factory in Hunan Province" (actually the East India Company tea plantation in Darjeeling, India). He offered 3x normal wages (6 taels/month vs 2 taels/month in Fujian), promise of return passage after 5 years, and 100-tael signing bonus (£12,500 modern equivalent, 4 years' normal salary).

The deception: Fortune told recruits they'd work in "Hunan" but actually transported them to India. By the time they realized (2-week voyage from Shanghai to Calcutta), they were stranded in a foreign country, couldn't return (execution risk), and had spent the signing bonus supporting their families.

Moral reckoning: Fortune's autobiography ("A Journey to the Tea Countries of China," 1852) justifies this as "liberating Chinese peasants from tyranny." Modern historians call it human trafficking and coerced labor. The tea makers' contracts were one-sided: no clause allowing them to quit, no legal protections in India (British law didn't recognize Chinese subjects' rights), and they were housed in plantation barracks under British supervision.

Most never returned to China. Six died in India (malaria, dysentery, accidents). Ten stayed permanently, married Indian women, and founded Chinese-Indian families. Their descendants still live in Darjeeling—family names Zhang, Wang, and Chen among Indian surnames, cultural hybrid identity.

The Impact: Destroying China's Tea Economy

Fortune's theft succeeded beyond the East India Company's wildest hopes:

1850: China produces 100% of world tea (220 million pounds annually). Britain imports 50 million pounds from China, pays £3.2 million.

1860: India produces 2 million pounds tea (Fortune's plants matured, processing mastered). China still dominates but British India tea is cheaper (£0.08/lb vs £0.15/lb Chinese).

1880: India produces 70 million pounds tea, Ceylon (Sri Lanka) 20 million pounds. China's export share drops to 50%. Britain saves £1.5 million/year.

1900: India produces 180 million pounds, Ceylon 150 million pounds. China's global market share: 15%. Britain imports only 8 million pounds from China (84% reduction). China's tea export revenue collapses from £12 million/year (1850) to £2.5 million/year (1900)—a £9.5 million annual loss (£6.2 billion modern equivalent).

This contributed to Qing Dynasty economic crisis, fueling the Taiping Rebellion (1850-1864, 20-30 million deaths), Opium Wars debt, and eventual collapse in 1911. Tea revenue loss weakened state capacity to suppress rebellions and pay foreign debts.

Meanwhile, British India tea made enormous profits: Darjeeling and Assam plantations returned 15-25% annual profit to investors (1860-1900). The East India Company paid Fortune's estate (he died 1880) £67,000 in profit-sharing (£44 million modern equivalent)—the £500/year spy salary was trivial compared to the value extracted.

Modern Parallels: Corporate Espionage Today

Fortune's methods are the template for modern intellectual property theft:

Trade secret theft via insiders: Fortune recruited Chinese tea makers = modern companies hiring competitors' engineers who bring proprietary knowledge. Coca-Cola, Google, Apple all have high-profile cases of employees recruited by competitors, accused of taking trade secrets.

Disguised reconnaissance: Fortune posed as merchant to study tea processing = modern "competitive intelligence" (spies posing as customers, investors, consultants to study factories and processes).

Technology smuggling: Fortune's Wardian cases smuggled plants = modern smuggling of semiconductor equipment, biotech samples, software source code. In 2018, Chinese scientist smuggled GMO rice seeds from U.S. to China in luggage—direct parallel to Fortune's plant theft.

State-sponsored industrial espionage: East India Company (quasi-state actor) funded Fortune's mission = modern governments fund corporate espionage (China's "Thousand Talents Plan" recruits Western scientists, NSA's economic espionage for U.S. companies, France's DGSE industrial spying).

The difference: today it's illegal (Economic Espionage Act 1996 in U.S., Computer Misuse Act 1990 in UK). In 1848, it was legal, celebrated, and knighted—Fortune received medals from Royal Horticultural Society and Royal Geographical Society, was honored as "Father of Indian Tea."

Conclusion: The Tea Heist That Built an Empire

Robert Fortune's 1848-1851 espionage mission was the most economically consequential botanical theft in history. He stole 20,000 tea plants, 32,000 seeds, complete processing knowledge, and 16 human experts who knew tea-making. This broke China's millennium-old tea monopoly, built the British India tea industry (which still produces 25% of global tea), and cost China's economy £6+ billion (modern equivalent) in lost revenue.

The mission demonstrated that intellectual property theft, if executed at scale with state backing, can destroy entire industries and shift global economic power. China's modern Belt and Road Initiative and technology transfer demands are, in part, economic revenge for 19th-century British thefts like Fortune's.

For other tea frauds and thefts: modern Taiwan smuggling, ancient Tea Horse Road bandits, and Victorian tea adulteration. See the full scope of tea criminology at Tea Criminology Hub.

Comments