The Boy from Auchenblae

James Taylor was born in 1835 in Kincardineshire, Scotland. The son of a wheelwright, he grew up in a modest rural setting. Like many young Scots of the Victorian era, he faced a choice: toil in the industrializing cities of Britain or seek fortune in the colonies.

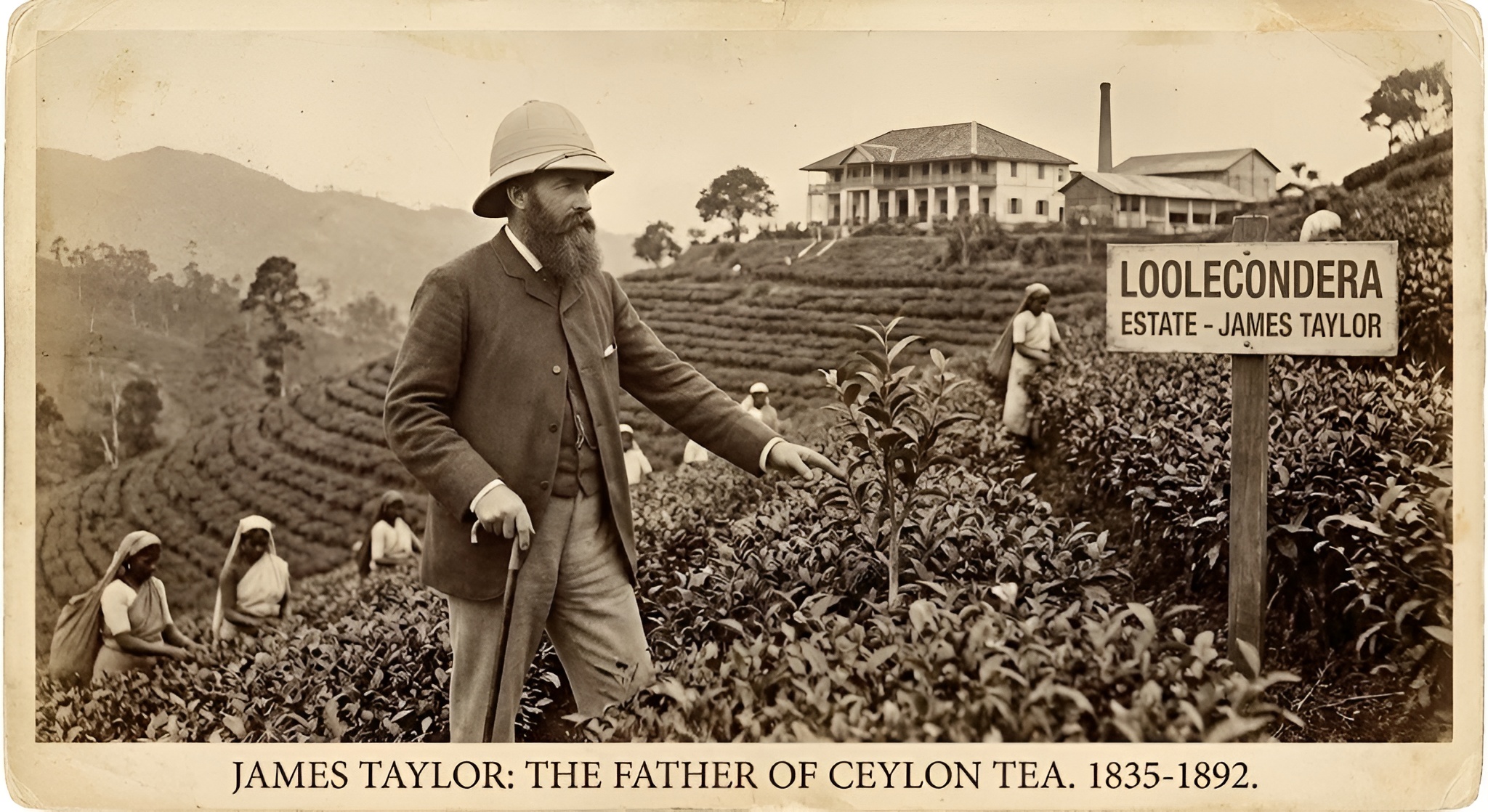

At the age of 17, Taylor signed a three-year contract as an assistant supervisor on a coffee plantation. He set sail for Ceylon in 1852. It was a journey of no return; remarkably, once Taylor set foot on the island, he would never see Scotland again. He was assigned to the Loolecondera Estate, located in the lush, misty Deltota valley near Kandy.

Life was not easy. The isolation was profound, the jungle was relentless, and the work was grueling. Yet, Taylor thrived. He was known for his incredible work ethic and his keen observational skills—traits that would eventually save the island's economy.

Expert Tip: Visiting Field No. 7

You can still visit Field No. 7 today. It is located about an hour's drive from Kandy. There is a small tea boutique there, and you can see "James Taylor's Seat," a rock formation where he reputedly sat to survey his estate. The tea bushes there are over 150 years old—gnarled and thick like trees, yet still producing leaves.

The Coffee Crash: "Devastating Emily"

To understand the magnitude of Taylor's achievement, one must understand the context of the 1860s. Ceylon was booming. Land was cleared at a ferocious pace to plant coffee bushes to feed the cafes of Europe. But nature has a way of correcting monocultures.

In 1869, a fungal disease known as Hemileia vastatrix appeared on the Madulsima plantations. The British planters, with grim gallows humor, nicknamed the fungus "Devastating Emily." It was a leaf rust that appeared as powdery orange spots on the underside of the leaves, stripping the bushes bare and preventing photosynthesis.

The spread was rapid and unstoppable. Within a decade, the coffee industry in Ceylon collapsed. Planters who had been millionaires faced bankruptcy. The banks crashed. The Oriental Bank Corporation went bust. Hundreds of British planters abandoned their estates and fled the island.

Expert Tip: The Indian Connection

While Ceylon was struggling with coffee, the British were already establishing tea in India using plants stolen from China by Robert Fortune. Read more about the British Raj and the Great Tea Heist here. Taylor would eventually use seeds from Assam to populate his fields, proving the Indian varietal was superior to the Chinese one for the tropics.

The Great Experiment: Field No. 7

James Taylor, however, stayed. Years before the coffee blight reached its peak, Taylor had already been experimenting. He was a natural botanist, curious about what else the fertile soil of Loolecondera could support. He tried growing Cinchona (for quinine), but his interest settled firmly on tea.

In the early 1860s, the Royal Botanic Gardens at Peradeniya gave Taylor a batch of tea seeds. Taylor planted them along the roadsides of the estate, treating them as garden experiments rather than a commercial crop.

In 1867—two years before the coffee rust appeared—Taylor made history. He cleared 19 acres of forest and planted the first commercial plot of tea in Sri Lanka. This legendary plot, known as Field No. 7, is still in existence today, and the original tea bushes are still being harvested.

Expert Tip: Plucking Standards

Taylor was obsessed with quality. He implemented the strict "two leaves and a bud" plucking standard—harvesting only the youngest, tenderest shoots. To learn more about how this affects flavor, read our guide on Tea Harvesting & Plucking.

Inventing the Process: The Veranda Factory

Growing tea is agriculture; making tea is engineering. The raw leaf must be withered, rolled, oxidized, and fired to become the black tea we recognize. In India, massive industrial machinery was being developed, but Taylor had none of that. He had to invent the process from scratch, using what he had available at Loolecondera.

The Innovations of Taylor

Taylor's "factory" was initially the veranda of his bungalow. He developed a process that is strikingly similar to the orthodox methods still used today:

- Rolling: The leaves were rolled by hand on tables on the veranda. Taylor's wrists famously became incredibly strong and calloused from hours of rolling leaves to break the cell walls.

- Firing: He built clay stoves and fired the tea over charcoal fires to stop the oxidation process.

- Mechanization: Realizing hand-rolling was inefficient, Taylor designed and built his own machinery. He created a water-wheel to power a simple rolling machine, arguably the first mechanized tea production in the country.

Expert Tip: Rolling Matters

Rolling is critical because it breaks the cell walls, releasing the enzymes that cause oxidation. Without this step, the tea would not turn black. To understand the chemistry behind this, check out our deep dive into Tea Rolling & Disruption.

The Birth of a Global Brand

Expert Tip: Lipton's Legacy

Thomas Lipton didn't just sell tea; he revolutionized packaging. Before him, tea was sold loose from chests. Lipton sold it in consistent, pre-weighed packets. This guaranteed freshness and quality, a standard we still expect today when buying Ceylon Tea.

The Legacy: The Seven Regions of Ceylon Tea

Taylor's success proved that tea could thrive in the hill country. But as planting spread across the island, planters discovered that the island's incredible biodiversity created distinct flavor profiles based on altitude. Today, Sri Lanka is divided into seven distinct tea regions, each with its own "terroir."

1. Kandy (Mid-Grown)

This is where it all began. The teas from Kandy, grown between 2,000 and 4,000 feet, are full-bodied, robust, and copper-toned. They are strong but not overpowering, making them the perfect base for flavored teas or Iced Tea recipes.

2. Nuwara Eliya (High-Grown)

Known as the "Champagne of Ceylon Teas," this region sits at the highest elevation (over 6,000 feet). The cool climate and mist produce a tea that is incredibly light, pale gold, and delicately floral. It is best drunk black with a slice of lemon.

3. Dimbula (High-Grown)

Located on the western slopes, Dimbula teas are defined by the monsoon seasons. They strike a balance between flavor and strength, often described as "refreshingly mellow." This is the classic profile found in many English & Irish Breakfast blends.

Expert Tip: Terroir Explained

Why do these regions taste different? It's all about Terroir—the combination of soil, climate, and altitude. High-grown teas grow slower due to the cold, concentrating the flavor. Low-grown teas grow fast in the heat, creating a stronger, darker leaf. Learn more in our Tea Regions Guide.

A Lonely End

Despite his monumental success, James Taylor remained a humble, salaried estate manager. He did not own Loolecondera; he worked for the company that did. He lived a solitary life, never marrying, his life revolving entirely around his tea bushes.

In 1892, at the age of 57, Taylor contracted dysentery. His death was sudden and shocking to the planting community. Legend has it that 24 men carried his coffin all the way from his estate to the Mahaiyawa Cemetery in Kandy, a journey of over 20 miles, as a mark of respect.

His tombstone bears a simple inscription: "He was the pioneer of the tea and cinchona enterprises in this island."

Comments