1. Biosynthesis: The Strecker Degradation

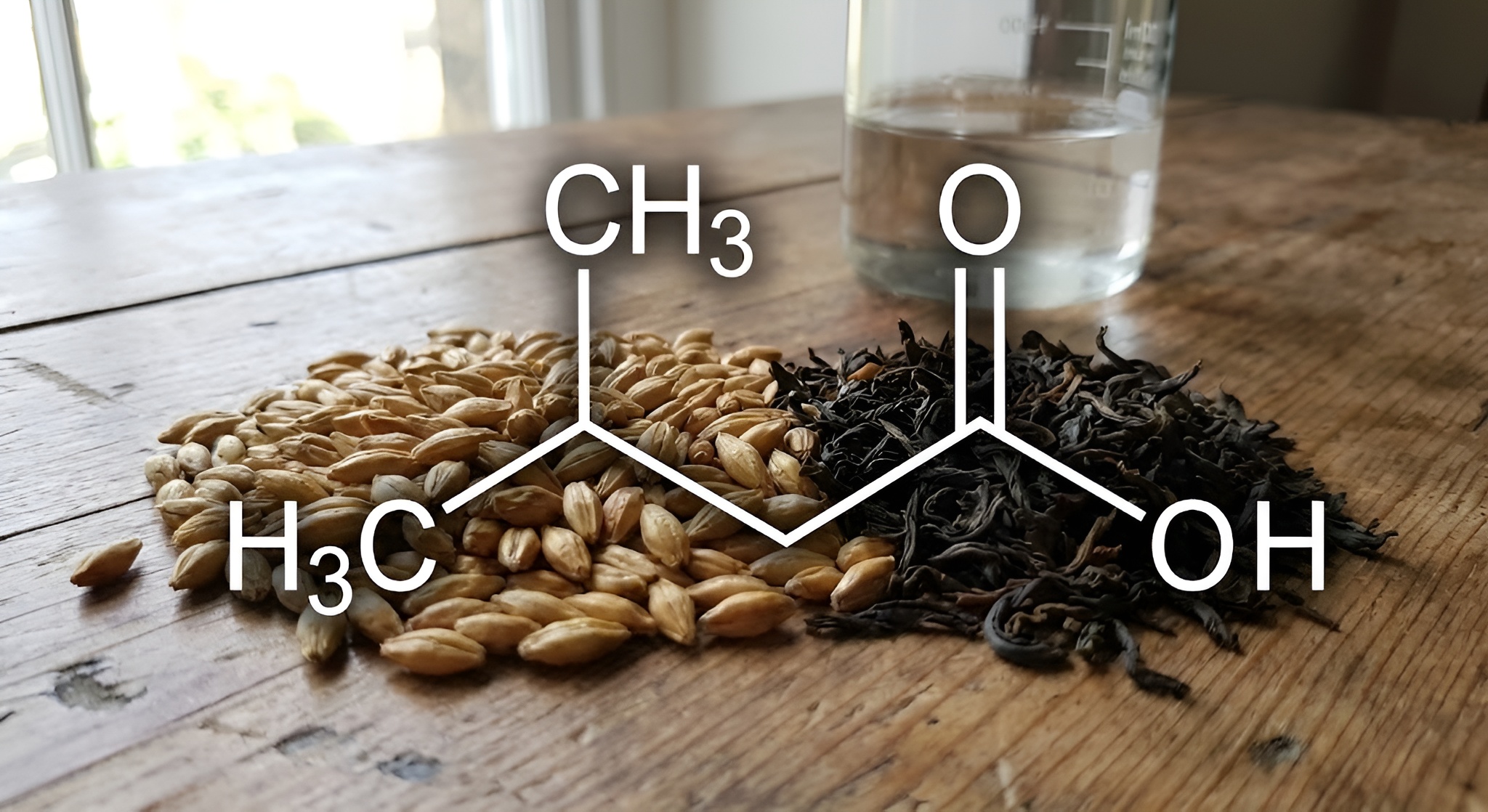

Unlike the floral terpenes (which are released from glycosides), Isovaleraldehyde is born from protein destruction.

During the "Hard Wither" stage of Black Tea processing, proteins in the leaf break down into free amino acids. One specific amino acid, Leucine, is the parent of the malt flavor.

The Mechanism: During oxidation, enzymes (polyphenol oxidase) create reactive quinones (the compounds that turn the leaf brown). These quinones attack Leucine in a process called Strecker Degradation.

The result is the removal of carbon dioxide and ammonia from Leucine, transforming it into the volatile aldehyde: 3-methylbutanal (Isovaleraldehyde).

This is why Green Tea (which is not oxidized) never tastes malty. You cannot have malt without the chemical violence of oxidation.

2. The Assamica Advantage: Why China Tea Isn't Malty

You can process Chinese tea (Keemun) as black tea, but it will taste fruity or smoky, rarely malty. Why?

Genetics: The Camellia sinensis var. assamica plant—native to the hot, humid jungles of Northeast India—has a different chemical baseline. It has significantly higher levels of Leucine and Valine (amino acids) in its sap compared to the sinensis variety.

The TRRF-1 Clone: Modern Assam plantations use specific clones like TRRF-1 or TV1. These have been bred over decades not just for yield, but for their ability to generate massive amounts of Isovaleraldehyde during the rapid oxidation of the monsoon harvest.

Expert Tip: Why Second Flush is Maltier

Just like with Geraniol in Darjeeling, the Second Flush (Summer Harvest) in Assam is prized over the First Flush. The intense heat and humidity of the Brahmaputra Valley in June accelerates the enzymatic breakdown of Leucine, creating the "Tippy Golden Flowery Orange Pekoe" (TGFOP) that defines a premium malty cup.

3. CTC Processing: The Flavor Engine

While Orthodox (whole leaf) Assam exists, the global demand for "Strong Tea" led to the invention of CTC (Crush, Tear, Curl) processing in the 1930s.

How it Works: The leaves are passed through metal rollers with sharp teeth that shred the cellular structure completely.

The Chemical Impact: This total maceration mixes the enzymes and amino acids instantly and violently. The reaction rate of Strecker Degradation skyrockets. This creates a tea that is incredibly high in Isovaleraldehyde (Malt) and Thearubigins (Color/Body) but low in delicate floral notes (Linalool), which are destroyed by the heat generated during the crush.

| Tea Style | Leaf Type | Malt Level | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assam CTC | Shredded Pellets | Extremely High | Builder's Tea, Masala Chai |

| Assam Orthodox | Whole Leaf | Medium-High | Drinking Black |

| Keemun (China) | Whole Leaf | Low (Fruity/Wine) | gongfu brewing |

| Darjeeling | Whole Leaf | Low (Muscatel) | Drinking Black |

4. The Milk Factor: Why Malt Needs Dairy

Why do we add milk to Assam but not to Oolong?

Casein Binding: Milk contains a protein called Casein. When added to tea, Casein binds to Tannins (bitterness), smoothing out the astringency.

However, Casein also binds to many aroma molecules, muting them. Isovaleraldehyde is different. It is a potent, fat-soluble aldehyde that seems to "cut through" the creamy texture of milk. While floral notes (Linalool) get lost in the fat, the heavy "bready" notes of Isovaleraldehyde are amplified by the lactose sweetness of milk. This is the chemical secret of the "Builder's Brew."

Find the Ultimate Breakfast Brew

We have tested the strongest, maltiest Assams on the market to find the ones that stand up to milk and sugar. Discover our top picks for a true "morning jolt."

Best Malty Teas

Comments