Introduction: A Cup of Controversy

On January 12, 1946, the London Evening Standard published an essay that would become the Magna Carta of British tea brewing. Orwell opened with a simple observation: "Tea is one of the mainstays of civilization in this country... but the best manner of making it is the subject of violent disputes."

This wasn't just about taste. In 1946, Britain was exhausted. The Empire was fracturing, cities were rebuilding from the Blitz, and rationing was a daily reality. A good cup of tea wasn't a luxury; it was the fuel that kept the nation running. Orwell’s rules weren’t just recipes; they were a plea for order, dignity, and maximizing the utility of a precious resource.

Rule 1: "Use Indian or Ceylonese Tea"

"One should use Indian or Ceylonese tea. China tea has virtues... but there is not much stimulation in it. One does not feel wiser, braver or more optimistic after drinking it."

The Historical Context

Orwell’s dismissal of Chinese tea is entirely a product of 1940s geopolitics. For centuries, "tea" meant Chinese tea. But by the 20th century, the British Empire had developed massive plantations in India (Assam/Darjeeling) and Ceylon (Sri Lanka). These colonies produced darker, maltier teas that shipped well and tasted consistent.

During the war, the government controlled tea purchasing. They prioritized robust Indian teas that could be diluted with milk and sugar to stretch rations. Chinese tea, with its delicate floral notes, was seen as "fancy" or "weak."

The Science of "Stimulation"

Orwell equates "quality" with "caffeine." He isn't looking for flavor nuance; he wants a drug. He admits Chinese tea is "economical" (you can drink it without milk), but he claims it lacks the "kick" to make you brave.

Is he right? Generally, yes. Assam tea (Camellia sinensis var. assamica) typically contains higher caffeine levels than Chinese varieties (Camellia sinensis var. sinensis). The broad leaves of the Assam plant produce a liquor that is bold, tannic, and astringent—exactly what Orwell needed to finish a manuscript.

Expert Tip: The Exception

If Orwell tried a really smoky Lapsang Souchong, he might have changed his mind. It’s got the punch he was looking for, just with smoke instead of pure caffeine. Lapsang was actually Sherlock Holmes's spiritual tea, offering intensity without the colonial baggage.

Rule 2: "Tea Out of an Urn is Always Tasteless"

"Tea should be made in small quantities - that is, in a teapot. Tea out of an urn is always tasteless, while army tea, made in a cauldron, tastes of grease and whitewash."

The Chemistry of Staling

Orwell is attacking the institutionalization of tea. The "Urn" represents the canteen, the army mess hall, and the loss of individuality. But chemically, he is spot on.

Tea contains polyphenols (tannins). When tea is kept hot for hours in a metal urn, these compounds oxidize rapidly. The liquid darkens, becomes muddy, and develops a metallic tang. Furthermore, volatile aromatic compounds (the stuff that smells nice) evaporate within minutes. Urn tea is essentially hot, brown, tannic water with no soul.

Material Matters: China vs. Earthenware

Orwell insists on a teapot made of china or earthenware. Why?

- Thermal Mass: Earthenware (like the classic Brown Betty) retains heat. It keeps the water near boiling point for the full 3-5 minute steep.

- Neutrality: Metal teapots (silver or pewter) can impart ions into the water, altering the flavor. Enamel pots chip, leading to rust.

If you want to brew like Orwell, ditch the stainless steel thermal carafe and get yourself a chunky ceramic pot. See our Guide to Teapots.

Rule 3: "The Pot Should be Warmed Beforehand"

"This is better done by placing it on the hob than by the usual method of swilling it out with hot water."

The Thermodynamics of the Pour

Pre-heating is non-negotiable. If you pour boiling water (100°C) into a cold ceramic pot (20°C), the ceramic acts as a heat sink. The water temperature will instantly drop to around 85°C. For delicate green tea, this is fine. For the robust black tea Orwell loves, it’s a disaster.

Black tea requires high heat to extract the Thearubigins (the red pigments that give body). If the water is too cool, the tea will be thin and flat. By pre-warming the pot, you ensure the water stays hot enough to do its job.

The Danger Zone

However, putting a ceramic teapot directly on a stove burner ("the hob") is a great way to explode your teapot due to thermal shock or uneven heating. We recommend sticking to the "swill" method: fill the pot with boiling water, let it sit for a minute, dump it out, then add your tea.

Rule 4: "The Tea Should be Strong"

"Six heaped teaspoons would be about right... one strong cup of tea is better than twenty weak ones."

The Ratio of Rationing

Orwell suggests six heaped teaspoons for a quart (approx 1 liter) pot. Modern standards usually suggest one teaspoon per cup (250ml), plus "one for the pot." Orwell’s ratio is nearly double the modern strength.

This is "Builder's Tea" taken to the extreme. In 1946, the tea ration was 2oz per week per person. Orwell is suggesting that you use a significant chunk of your weekly allowance in a single pot. This is an act of defiance. It says: "I may be poor, but I will not drink dirty water." It creates a liquor so thick and tannic that it requires milk to bind the proteins, creating a rich, savory mouthfeel.

Rule 5: "No Strainers, Muslin Bags or Other Devices"

"The tea should be put straight into the pot... devices to imprison the tea."

The Agony of the Leaf

Orwell was writing before the tea bag conquered the world. He viewed infusers as prisons. He was scientifically correct. For tea to brew properly, the dried leaf needs to rehydrate and unfurl. This expansion is called "the agony of the leaf."

When leaves are crammed into a small metal ball or a paper bag, water cannot circulate through them. The center of the mass remains dry, while the outer layer over-extracts. Orwell preferred to drink a few floating leaves ("tea dust") rather than compromise the flavor extraction. Read: Why Tea Bags are the Enemy.

Rule 6: "Take the Pot to the Kettle"

"The water should be actually boiling at the moment of impact."

Oxygen and Energy

This is the most critical technical rule. Water must be at a "rolling boil" when it hits the leaves. If you turn off the kettle and walk across the kitchen to the teapot, the water loses crucial degrees of heat.

Furthermore, Orwell implies you shouldn't re-boil water. Fresh water contains dissolved oxygen, which helps lift the aromatic compounds of the tea. Re-boiled water is flat and de-oxygenated, leading to a dull tasting brew. Learn why reboiling ruins tea here.

Rule 7: "Give the Pot a Good Shake"

"Afterwards allowing the leaves to settle."

The Concentration Gradient

This rule horrifies formal tea drinkers, but it makes sense physically. As tea steeps, the water nearest the leaves becomes saturated with solubles. This dense liquid sinks to the bottom. The water at the top remains weak.

Shaking the pot (or stirring) ensures an even extraction (homogenization). Without this step, your first cup is weak water, and your last cup is bitter sludge. Orwell’s insistence on letting the leaves settle afterwards is the key—he acknowledges the chaos of loose leaf brewing but demands the patience to manage it.

Rule 8: "Drink Out of a Cylindrical Cup"

"The breakfast cup... not the flat, shallow type."

Surface Area vs. Volume

This is a rejection of aristocracy. The "flat, shallow type" refers to fine bone china teacups used in high society Afternoon Tea. These cups are designed to cool the tea quickly so it can be sipped politely between bites of cucumber sandwich.

Orwell wants a mug. A cylindrical cup has a lower surface-area-to-volume ratio, meaning less heat escapes via evaporation. The tea stays hot longer. This is a functional vessel for a writer working late into the night, not a prop for a social gathering.

Expert Tip: The Psychology of the Mug

There is psychological comfort in wrapping your hands around a warm cylindrical mug. It is a tactile experience of warmth and safety—exactly what Orwell sought in the bleak 1940s.

Rule 9: "Pour the Cream off the Milk"

"Milk that is too creamy always gives tea a sickly taste."

The Lipids Problem

In 1946, milk was delivered in glass bottles, and it was not homogenized. A thick layer of cream would separate and rise to the top ("top of the milk").

Orwell argues that this heavy fat content coats the tongue (a lipid film), blocking the taste buds from perceiving the astringency of the tea. He wants the milk to provide color and body, but not to mute the flavor. He is essentially inventing semi-skimmed milk decades before it became popular. He wants the tea to remain "snappy," not become a dessert.

Rule 10: "Pour Tea into the Cup First" (Milk Last)

"This is one of the most controversial points of all... by putting the tea in first and stirring as one pours, one can exactly regulate the amount of milk."

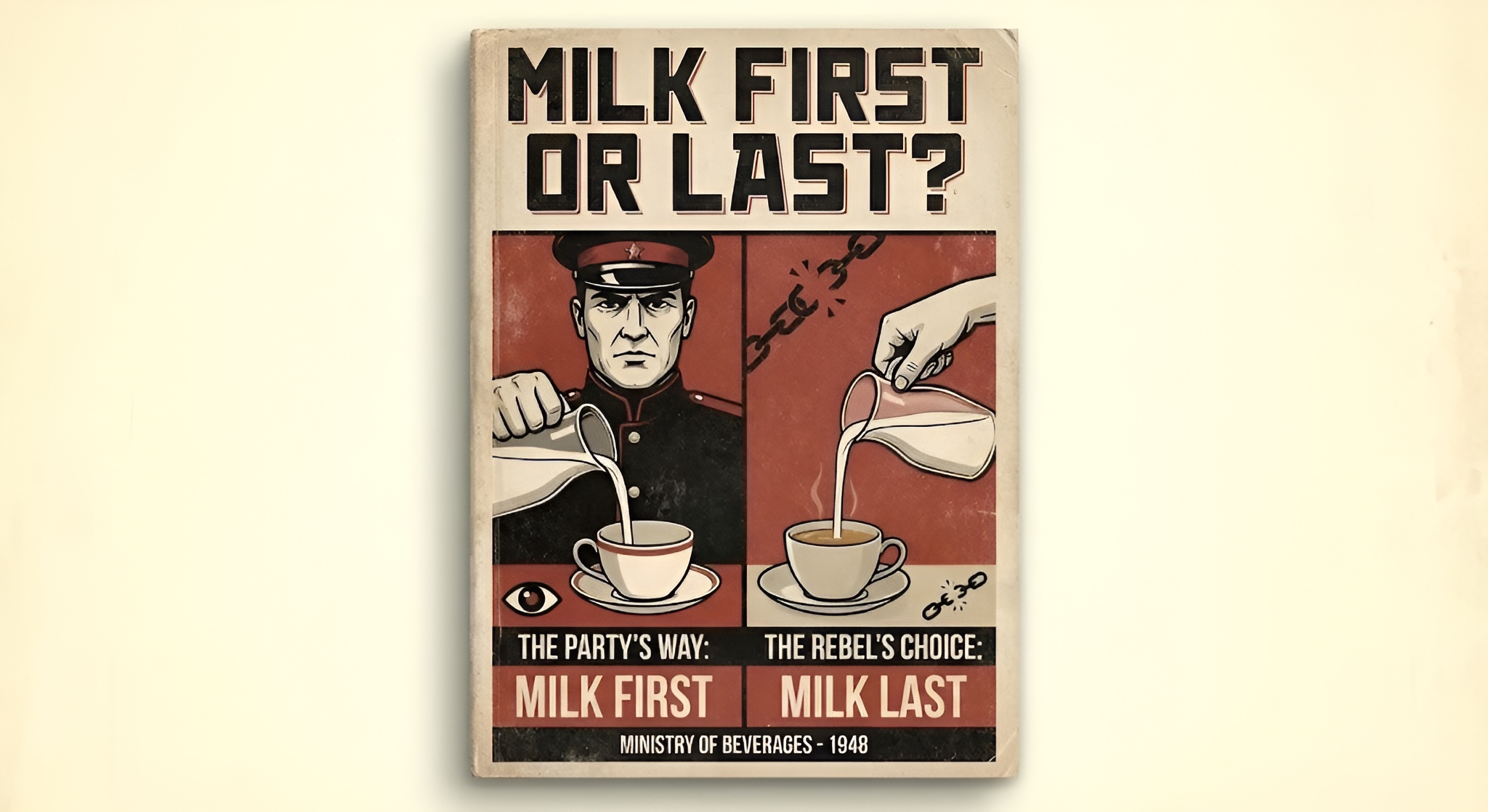

The Great Debate: Miffy vs. Tiffy

This is the Civil War of British tea.

- Miffy (Milk In First For You): Historically, working-class households poured milk first because their cheap earthenware cups might crack if boiling tea hit them directly. The milk acted as a coolant. Science also supports this: pouring hot tea into milk prevents the milk proteins from scalding (denaturing).

- Tiffy (Tea In First For You): Aristocrats with fine bone china didn't worry about cracking. They poured milk last. Orwell sides with the aristocrats here, but for a practical reason: Regulation.

Orwell argues that if you pour milk first, you are guessing the ratio. If you pour tea first, you can add milk drop by drop until the color is perfect. For a control freak like Orwell, visual precision trumped protein chemistry.

Rule 11: "Tea Should be Drunk Without Sugar"

"How can you call yourself a true tea-lover if you destroy the flavour of your tea by putting sugar in it? It would be equally reasonable to put in pepper or salt."

The Purist Manifesto

Orwell ends with a challenge. He argues that tea is meant to be bitter, just as beer is meant to be bitter. Sugar is a mask for bad tea. If you sweeten it, you aren't tasting the leaf; you are tasting hot syrup.

This rule separates the "Tea Drinker" (who needs a warm, sweet comfort beverage) from the "Tea Lover" (who appreciates the botanical complexity of the plant). However, given that Orwell advocates for a brew strong enough to strip paint (Rule 4), his insistence on drinking it black/unsweetened suggests a level of masochism. It is a demand for stoicism. Life is bitter; drink it up.

Expert Tip: The Russian Style

Orwell allows one exception: "Russian Style." This refers to tea taken with a slice of lemon, or with a sugar cube held between the teeth (not dissolved in the cup). The acid of the lemon cuts the tannins differently than sugar, preserving the complexity.

Related Reading in Literature & Film

- Emma: Tea as Social Currency in Regency England

- The Remains of the Day: Butler's Tea Service as Emotional Repression

- Brideshead Revisited: Tea, Class, and Aristocratic England

- Agatha Christie's Tea Murders: Poison and Afternoon Tea

- Cranford: Victorian Ladies Governing Through Tea

- Narnia's Mr. Tumnus Tea: CS Lewis's Moral Infrastructure

- Doctor Who's Tea Culture: 60 Years of British Tea

- Sense and Sensibility: Tea as Social Survival Exam

Conclusion: A Man of His Time

George Orwell's 11 rules are more than a recipe; they are a snapshot of British resilience. They reject the fancy, the institutional, and the weak. They demand attention to detail even when the world is crumbling.

While we might now have variable-temperature kettles, filtered water, and access to exquisite Oolongs that Orwell never dreamed of, his core philosophy remains true: Tea is serious business. It deserves to be made with care. Whether you put the milk in first or last, do it with conviction.

Brew Like Orwell

Want to test Rule #1? We reviewed the strongest Indian and Ceylonese teas that would make Orwell proud.

Review: Best Strong Assam Teas

Comments