1. Thermal Protection: The Original Function

Teacup saucers emerged in 18th-century Europe as thermal barrier: early teacups (Chinese porcelain imports, 1600s-1700s) lacked handles (handles added later), making hot cups painful to hold directly. The saucer solved this: set hot cup on saucer, pick up saucer instead (larger surface area distributes heat, fingers avoid contact with hot porcelain). This parallels modern coffee sleeves (cardboard barrier protecting hands from hot cup)—saucer is 18th-century version of same thermal problem.

The physics: porcelain has high thermal conductivity (1-3 W/m·K), meaning heat transfers rapidly from tea to cup exterior. Human pain threshold is ~45°C skin temperature; tea served at 80-90°C easily exceeds this. Holding cup by rim (minimal contact) only works briefly—prolonged grip causes burns. Saucer provides alternative: larger holding surface (3-4× cup rim area), cooler temperature (saucer bottom exposed to air, cools faster than cup walls in contact with hot liquid), and psychological comfort (less direct heat sensation even if temperature similar).

Modern parallel: Japanese tea ceremony uses both hands to cradle bowl (distributes heat, prevents burns)—different ergonomic solution to same thermal problem. Indian kulhar clay cups have lower thermal conductivity (terracotta insulates better than porcelain)—material choice eliminates need for saucer. Western solution was adding intermediary object (saucer) rather than changing cup material or holding technique.

| Historical Period | Cup Type | Saucer Function | Cultural Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1650-1750 (Early European Tea) | Chinese export porcelain, no handles, small bowls | Primary holding surface (cup too hot to grasp directly) | Wealthy elite imitating Chinese tea practice (minimal understanding) |

| 1750-1850 (Victorian Era) | European porcelain with handles added, larger capacity | Secondary cooling surface (saucer-drinking ritual—pour tea into saucer to cool) | Etiquette codification, class signaling through table manners |

| 1850-1950 (Modern Formalization) | Standardized teacup + handle, matched sets | Drip catcher (spoon rest, prevents table stains), decorative complement | Middle-class aspiration, tea service as status symbol, matched china sets |

| 1950-present (Casual Decline) | Mugs (thick-walled, insulated), disposable cups | Obsolete for most users (mugs don't need saucers—handles sufficient) | Informality, convenience culture, formal tea service niche/nostalgic |

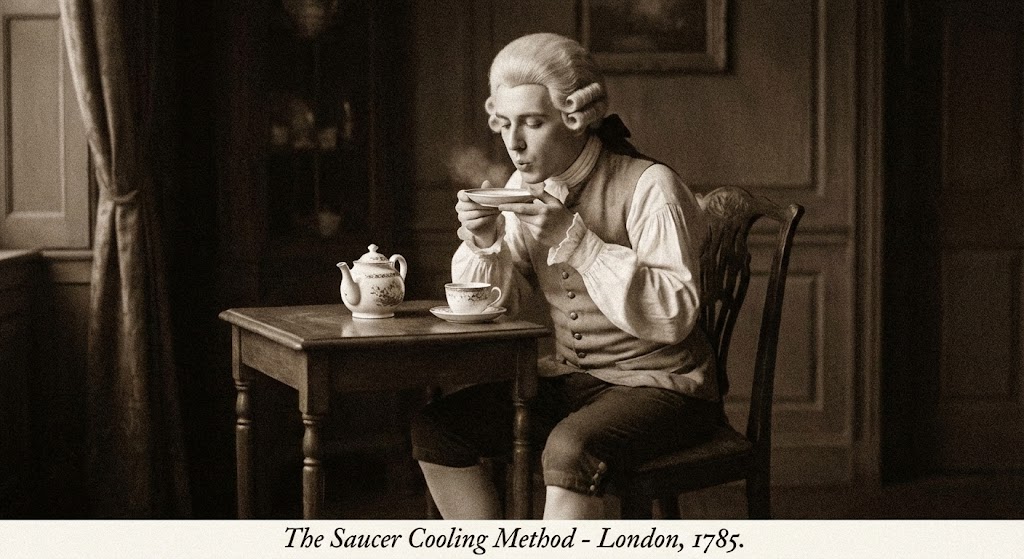

2. The Saucer-Drinking Ritual: Cooling by Surface Area

In 18th-19th century Europe and America, common practice was pouring tea from cup into saucer, drinking directly from saucer (slurping from shallow dish). The functional logic: saucer's wide, shallow design maximizes surface area (liquid spreads thin, more exposure to air), accelerating evaporative cooling. A 6cm diameter cup has ~28cm² surface area; a 15cm saucer has ~177cm²—6× more surface for heat dissipation. Tea cools in saucer 3-5× faster than in cup (from 85°C to drinkable 60-65°C in 2-3 minutes vs. 8-10 minutes in cup).

The physics of evaporative cooling: heat transfer rate follows Newton's Law of Cooling, $ q = hA(T_s - T_\\infty) $, where $ q $ is heat transfer rate, $ h $ is convective heat transfer coefficient, $ A $ is surface area, $ T_s $ is tea surface temperature, $ T_\\infty $ is ambient air temperature. Increasing $ A $ (surface area) by 6× increases cooling rate proportionally—saucer-drinking is applied thermodynamics (pre-scientific era folk knowledge of heat transfer principles).

The social evolution: saucer-drinking was respectable through ~1850s (seen in period literature, etiquette manuals describing technique). By late 1800s, Victorian etiquette declared it vulgar (noise, messiness, lower-class association). The prohibition: proper society drinks from cup only; saucer is purely decorative/utilitarian (drip catch). But practice persisted in working-class contexts and rural areas (American frontier, British factories) into early 1900s—class divide between \"refined\" slow sipping from cup vs. \"crude\" fast cooling in saucer. This parallels builder's tea class tensions (working-class tea methods judged by middle-class standards).

Expert Tip: The Surviving Saucer-Drinking Cultures

Saucer-drinking persists in specific regional contexts: Turkey/Iran: Pouring tea into saucer still common (especially older generations), called \"çay tabağı\" (tea plate) drinking—functional in hot climates (need to cool tea quickly). Russia: Traditional podstakannik (glass holder) tea often poured into saucer for cooling—rural areas maintain practice. Eastern Europe: Grandparent generation in Poland, Hungary, Czech areas sometimes saucer-drink (cultural continuity from pre-WWII era). If traveling in these regions and offered tea in saucer, don't assume mistake—may be intentional traditional service. Slurp gently from saucer edge (minimizes noise while getting cooler tea).

3. Spoon Rest and Drip Management

Once saucer-drinking declined (late 1800s), saucer's function shifted: becomes resting place for wet teaspoon after stirring (prevents dripping on tablecloth/table), catches overflow drips from cup rim (when overfilled or sloshing), and holds used tea bag temporarily (before disposal—keeps wet bag off clean surface). These utilitarian functions justified saucer's continued existence even after primary thermal function obsolete (cups now have handles, less need for cooling intermediary).

The drip physics: capillary action draws liquid up spoon stem (residual tea clings to metal surface), gravity pulls droplets downward. Without saucer, drips fall on table (stains wood, ruins finishes, creates sticky mess). Saucer intercepts drips, contains them in disposable/cleanable area. This parallels tea tray function in Gongfu brewing—dedicated overflow containment preventing mess migration.

The aesthetic dimension: matched cup-and-saucer sets (same pattern, coordinated design) became mark of quality tea service. Mismatched pieces signaled poverty/carelessness (can't afford complete set, or broke pieces individually). The completeness fetish: Victorian-era tea sets included 6-12 cup-saucer pairs, teapot, sugar bowl, creamer—all matching. Missing even one saucer devalued entire set. This formalism created saucer's permanence: not functional necessity, but social requirement (proper tea service demands saucers, regardless of actual use).

4. Porcelain Traditions: Chinese vs. European Design

Chinese tea culture (origin of porcelain technology, 600-900°CE development) traditionally used handleless cups without saucers: small bowls (50-100mL capacity), held with both hands or fingers on rim, no separate saucer component. The gaiwan (lidded bowl, Ming Dynasty innovation) has integral saucer (bottom plate for stability, drip catch), but Western-style separate saucer concept absent—Chinese design assumes careful handling, minimal spillage, acceptance of heat (brief discomfort tolerable).

European adoption (~1650s onward) added saucers: Reason 1 - Larger tea volumes: Europeans brewed weaker tea, drank larger quantities (200-300mL cups vs. Chinese 50-100mL)—more liquid = more spills, saucer catches errors. Reason 2 - Different table manners: Chinese tea ceremony emphasizes controlled precision (spilling is failure), European social tea prioritizes conversation over technique (spills inevitable, saucer accommodates imperfection). Reason 3 - Furniture protection: Expensive European wood furniture (French polish, marquetry) more vulnerable to water damage than Chinese lacquer tables—saucer protects investment.

The cultural adaptation: Europeans took Chinese cups (beautiful, exotic, high-status imports) but modified context\u2014added saucers for European use-case (casual drinking, furniture protection, larger volumes). This parallels Hong Kong milk tea (British tea tradition adapted to Chinese materials/techniques) and American sweet tea (British tea transformed by Southern climate/culture). Cultural borrowing always involves transformation.

5. The Mug Revolution: Why Saucers Became Optional

Modern mugs (1940s-present, thick ceramic with sturdy handle) eliminated saucer necessity: Thermal insulation: Thick walls (5-8mm ceramic vs. 2-3mm fine porcelain) reduce heat transfer—mug exterior stays cooler, comfortable to hold. Large handles: Robust grip (2-3 finger capacity vs. delicate teacup's 1-2 finger loop) distributes force, easier to lift heavy liquid loads. Stability: Wide base (low center of gravity) prevents tipping—less spillage, reduced saucer need. Casual aesthetic: Mugs signal informality (no matching required, individual expression via novelty designs), saucers signal formality (complete sets, coordinated patterns).

The generational shift: older generations (pre-1960) learned tea in cups-and-saucers (formal service, matching china), younger generations (post-1980) default to mugs (microwave-safe, dishwasher-durable, individualistic). The formality decline: tea transitioned from special occasion (afternoon tea ritual, guest service, social performance) to everyday utility (morning caffeine, office beverage, convenience). Saucers became optional affectation (nostalgic, twee, or genuinely preferring formal service), not standard equipment.

| Vessel Type | Wall Thickness | Thermal Conductivity | Saucer Necessity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fine Porcelain Teacup | 2-3mm (delicate, translucent) | High (1-3 W/m·K)—exterior gets very hot | Essential (cup too hot to hold, saucer provides handling surface) |

| Bone China Cup | 2-4mm (stronger than porcelain, still thin) | Moderate-high (stronger than porcelain, slightly better insulation) | Recommended (handle helps, but saucer still useful for drips/spoon) |

| Stoneware Mug | 5-8mm (thick, sturdy, heavy) | Low (0.5-1 W/m·K)—insulates well, exterior stays cooler | Optional (mug handle sufficient, walls insulate, saucer only for aesthetics) |

| Double-Wall Glass | 3mm each wall + air gap (total ~10mm insulation) | Very low (air gap is excellent insulator, 0.024 W/m·K) | Unnecessary (exterior remains cool enough to touch comfortably) |

Expert Tip: When to Actually Use Saucers Today

Use saucers when: (1) Serving guests formally (afternoon tea, special occasions)—shows effort, signals hospitality. (2) Using antique/delicate teacups (thin porcelain, family heirlooms)—saucer protects both cup (stable platform) and furniture (drip catch). (3) Drinking very hot tea (85°C+, immediate consumption)—saucer allows cooling without waiting. (4) Outdoor/unstable surfaces (garden tea, picnic tables)—saucer provides wider base, prevents tipping. Skip saucers when: (1) Using mugs (unnecessary, just extra washing). (2) Casual/solo drinking (no audience for formality). (3) Space-limited (airplane tray tables, packed dishwasher). (4) Dishwasher-loading optimization (saucers take excessive rack space). Saucers are tool, not requirement—deploy strategically, not automatically.

6. Regional Persistence: Where Saucers Still Matter

United Kingdom: Formal afternoon tea maintains cup-and-saucer tradition (hotels, tea rooms, traditional households). Saucer holds biscuit/shortbread (separate plate unnecessary), catches crumbs from dunking. Working-class \"builder's tea\" uses mugs (no saucers), creating class distinction through tableware. Middle East: Turkish çay served in small tulip glasses on saucers (saucer catches sugar spills, provides cooling surface). Iranian tea service similar—saucer holds sugar cube (absorbs drips from ghand pahlou ritual). India: Chai stalls use cups-and-saucers (saucer for cooling scalding chai, practical in hot climate). Kulhar clay cups are exception (no saucer, cup itself disposable).

Japan: Western-style tea (kōcha 紅茶) uses cups-and-saucers (European influence, formal service), but traditional sencha uses handleless cups without saucers (yunomi placed directly on table/tray). The dual system: imported European tea etiquette coexists with native Japanese tea culture—different vessels for different contexts. United States: Saucer use largely obsolete outside specific contexts (Southern tea culture, vintage-themed cafes, grandmother's house). Mainstream American tea (iced, bagged, casual) rarely involves saucers—cultural shift toward convenience over formality.

7. Saucer Design Evolution: From Functional to Decorative

Early saucers (1700s) were purely functional: plain white porcelain, deep well (10-15mm depth to hold liquid when saucer-drinking), minimal decoration. Victorian era (1850-1900) added ornamentation: floral patterns, gilt edges, coordinated with cup design (matching not required initially, became standard later). Art Nouveau/Deco periods (1890-1940) introduced artistic saucers: asymmetric shapes, bold colors, artist-designed limited editions—saucer as canvas, not just utilitarian platform.

Modern design trends: Minimalist saucers: Pure white, no pattern, focus on form (Japanese-influenced aesthetic, Scandinavian design). Novelty saucers: Quirky shapes (shaped like leaves, animals, abstract forms), conversation pieces. Integrated designs: Cup-and-saucer as single sculptural object (handle extends to saucer, unified silhouette). Functional additions: Saucers with slots for cookies/tea bags, built-in spoon rests, stackable designs for storage efficiency.

The collectibility market: vintage saucer-cup sets (especially incomplete sets—orphaned saucers without matching cups) have odd value hierarchy. Complete matched set: highest value (collectors, functional use). Cup without saucer: medium value (usable solo, less formal). Saucer without cup: lowest value (cannot function alone, decorative only). But rare/beautiful saucers can exceed cup value—Art Deco saucers by famous designers (Clarice Cliff, Susie Cooper) collectible independently. The secondary market creates odd incentive: breaking sets sometimes more profitable (sell rare pieces individually to specialists).

8. Environmental and Practical Considerations

Saucer criticism from minimalist/environmental perspectives: Resource waste: Producing saucers requires materials (clay, glaze, energy for firing), doubling tea service's environmental footprint—cup alone is sufficient for function. Storage burden: Cup-and-saucer sets require 2× storage space (especially problematic in small apartments, cramped kitchens). Stacked cups more space-efficient than paired cup-saucer sets. Washing labor: Each saucer is extra dish to wash (doubles dishwashing time/water use for tea service). Breakage vulnerability: Fragile saucers chip easily (knocked off table, drawer jostling), creating incomplete sets (frustration when saucers break but cups survive, or vice versa).

The anti-saucer movement: minimalist lifestyle advocates recommend mug-only tea (fewer possessions, easier maintenance, adequate function). Marie Kondo approach: if saucers don't \"spark joy\" and rarely used, donate/discard (keep only if genuinely valued). But counter-argument: saucers enable formal hospitality (signaling care for guests, creating special occasions), and beauty/tradition have value beyond pure utility. The debate mirrors broader material culture tension: efficiency vs. ceremony, minimalism vs. abundance, practical vs. meaningful.

9. Making the Saucer Decision: When to Keep Them

Keep saucers if: (1) You regularly host formal tea (afternoon tea parties, traditional service for guests). (2) Own delicate antique cups (saucers protect investment, complete historical set). (3) Genuinely enjoy ritual (setting table beautifully, using inherited china, maintaining tradition). (4) Have storage space (not sacrificing needed space for rarely-used items). (5) Saucers have sentimental value (grandmother's set, wedding gift, family heirloom). Ditch saucers if: (1) Always drink from mugs (saucers unused, gathering dust). (2) Space-constrained (small kitchen, limited cabinet space). (3) Prefer casual tea (no formal service, convenience prioritized). (4) Hate extra dishes (minimalist dishwashing, efficiency-focused). (5) Saucers incomplete/mismatched (aesthetically unsatisfying, functionally adequate but visually cluttered).

Hybrid approach: Keep one nice cup-and-saucer set for special occasions (guest service, formal tea when desired), use mugs for daily drinking. This balances capability (can do formal service when wanted) with practicality (don't burden everyday routine with unnecessary items). Store formal set separately (display cabinet, special shelf), keep daily mugs accessible (counter rack, easy-access cabinet). The flexibility allows both modes: ceremony when meaningful, convenience when practical.

The broader lesson: tea culture offers spectrum from extreme formality (Japanese tea ceremony's rigid protocols) to pure utility (builder's tea in chipped mugs). Saucer use is personal choice along this spectrum—neither required nor forbidden, but conscious decision reflecting your relationship with tea. What matters: intentionality (knowing why you do/don't use saucers), not conformity to external rules. Your tea practice, your choices, your cups (and saucers, or not).

Comments