1. The Handleless Tradition: Chinese Porcelain Bowls

Chinese tea culture (origin of both tea and porcelain, 600s-900s CE as seen in Tang Dynasty tea practice) used handleless cups: small bowls (50-100mL capacity), held with fingers on rim or cradled in both hands. The design logic: Thermal feedback: Holding cup directly provides temperature information (too hot to hold = too hot to drink)natural warning system prevents burns, similar to Kashmiri chai's careful temperature handling. Aesthetic purity: Uninterrupted surface allows continuous decoration (painted dragons, calligraphy circle entire vessel without handle interruption), much like tea pets' unbroken glaze surfaces. Compact stacking: Handleless bowls nest efficiently (storage/transport advantage on tea clipper ships). Meditative ritual: Two-handed holding creates mindful moment (cannot multitask while drinking, forces attention to tea).

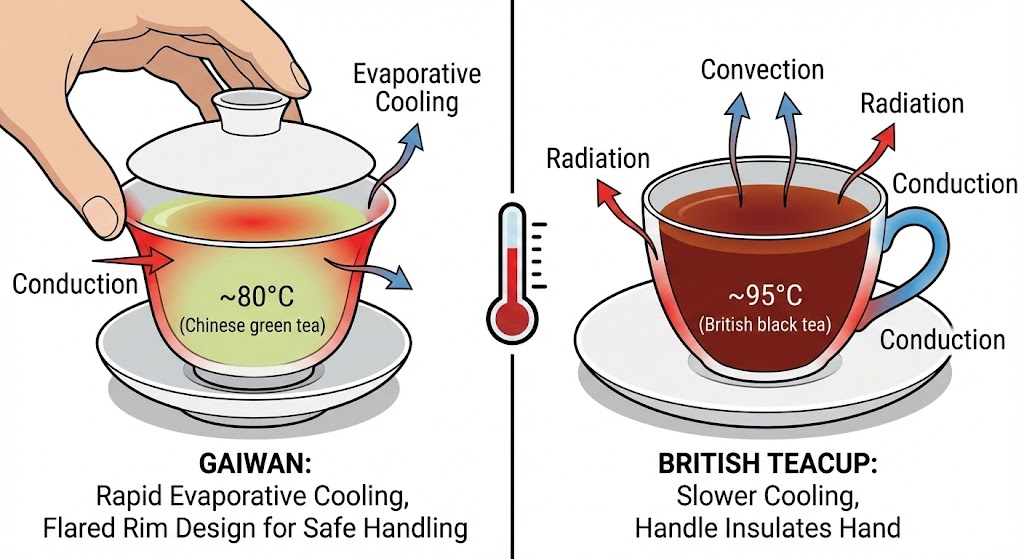

The gaiwan (?? gi wan, \"lidded bowl,\" Ming Dynasty ~1500s) refined handleless design: bowl + saucer + lid, held by gripping saucer edge while lid slightly open (allows sipping without removing lid, filters leaves). The three-fingered grip: thumb and middle finger hold saucer rim, index finger rests on lid knob (controls opening angle)elegant technique requiring practice. Modern Gongfu tea still uses gaiwans (skill demonstration, traditional authenticity), though Yixing teapots also common.

The thermal tolerance: Chinese tea ceremony accepts brief discomfort (hot cups train patience, build characterminor suffering as aesthetic value), similar to Song Dynasty whisking's arm fatigue or teh tarik's practice-required skill. This parallels Japanese tea room's designed discomfort (cramped space, temperature extremes as spiritual training). Western tea culture (particularly Victorian afternoon tea) rejected thisprioritized comfort, leading to handle invention. The philosophical divide: Eastern traditions embrace difficulty (physical challenge enhances experience, as in Gongfu's precision demands), Western approach removes obstacles (engineering solutions for comfort).

| Region/Era | Typical Cup Design | Holding Method | Cultural Values Reflected |

|---|---|---|---|

| China (Traditional) | Handleless bowl (50-100mL), porcelain, thin walls | Rim grip (3 fingers) or two-handed cradle | Meditative focus, aesthetic purity, thermal feedback (mindfulness) |

| Japan (Chanoyu) | Thick ceramic bowl (chawan), no handle, rustic texture | Two-handed cradle (distributes heat, reverential handling) | Humility (both-hands respect), wabi-sabi (imperfect beauty), ritual formality |

| Europe (1650-1750) | Chinese import bowls (no handles initially), then European copies | Initially mimicked Chinese (awkward, burns common), then demanded handles | Cultural borrowing (prestige of exoticism), eventual adaptation (comfort prioritized) |

| Europe (1750-1900) | Porcelain cup with delicate loop handle, 200-300mL | Pinky-out grip (performative refinement), single-handed | Class signaling (manners as status), gendered etiquette (feminized tea service) |

| Modern (1900-present) | Thick mug with sturdy handle, 300-500mL | Practical fist-grip or multi-finger loop | Efficiency (large volumes, fast drinking), informality (casual aesthetics) |

2. European Adoption: The 1750s Handle Innovation

European tea drinking began ~1650s (British East India Company imports via tea clipper races), initially using Chinese porcelain bowls (no handles, as imported). Early adopters mimicked Chinese technique (rim grip, two-handed holding), but found it impractical: Europeans drank larger volumes (200-300mL vs. Chinese 50-100mLheavier cups harder to hold by rim alone), weaker tea (lower temperature tolerance than Turkish ay's near-boiling service, less thermal training than Persian tea glass holding), and incorporated tea into existing table culture (wanted one-handed drinking while conversing, eating pastries at afternoon tea).

The handle innovation (~1750s, Meissen and English porcelain factories) added side loop: small curved handle attached to cup body, allows single-handed grip, insulates hand from hot porcelain. Early handles were tiny (\"ear\" handles, 2-3cm tall, one-finger loop), gradually enlarged to modern 2-3 finger capacity. The engineering challenge: attaching handle to thin porcelain without crackingrequired precise clay moisture matching (handle and cup body must shrink equally during firing, or join fails/cracks). Early handles often broke off (weak attachment points, thermal stress during use)took decades to perfect technique.

The thermal physics: handle acts as heat sink, drawing heat away from cup body through conduction, dissipating via convection to air (similar to teh tarik's cooling dynamics or kulhar cups' porous clay heat dissipation). But thin porcelain handles have low thermal mass (minimal heat capacity), so handle stays relatively cool despite contact with hot cup. Modern thermal modeling shows handle temperature ~15-2°C cooler than cup body (for 85C tea, handle ~40-4°Cbelow pain threshold). The key: small contact area (handle attaches at 2 points, minimizes thermal bridge), and exposure to air (convective cooling keeps handle surface temperature tolerable).

Expert Tip: The \"Pinky Out\" Myth Debunked

Extended pinky finger while holding teacup (\"pinky out\") is popularly believed to be proper etiquetteactually false. Victorian etiquette books specify: all fingers through handle loop, or index through loop with middle/ring supporting cup bottom, pinky naturally curled (not extended). The \"pinky out\" habit likely emerged from: (1) Tiny early handles (only 1-2 fingers fit, pinky had nowhere to go), (2) Imitating aristocracy (performative refinement taken to absurd extreme), (3) Satire crystallizing into norm (mocking upper-class affectation became perceived as actual upper-class behavior). Modern etiquette: pinky extended is considered affected/pretentious. Natural grip (whatever is comfortable, no performative gestures) is current standard. The lesson: many \"traditions\" are misunderstandings that calcifiedalways question received wisdom.

3. Handle Shapes: From Delicate Loops to Sturdy Grips

Teacup handle evolution reflects changing use-cases: 1750-1850 (Delicate loop): Thin circular/oval handles, 1-2 finger capacity, decorative curves (scrollwork, flourishes) echoing chabana's delicate aesthetics. Designed for: small refined sips (tea as leisure at Victorian tea gatherings, not hydration), wealthy users (servants handle heavy pots/kettles), display value (handle as ornament, not just function). Fragilebroke easily, required careful handling. 1850-1950 (Utilitarian C-shape): Thicker handles, 2-3 finger capacity, simple curves (less decoration, more strength) contrasting with builder's tea's sturdy mugs. Designed for: middle-class adoption (self-service tea, no servants), larger cups (200-300mL), durability (everyday use, not just special occasions). Sturdier but still breakable.

1950-present (Mug handle): Very thick D-shaped or rectangular loop, full-fist grip possible, often oversized (handle larger than necessary for stability margin), as seen in billy tea enamel mugs. Designed for: heavy ceramic mugs (500mL+ capacity like Hong Kong milk tea servings), microwave use (thick handle doesn't get as hot as thin loops), dishwasher durability (resists mechanical stress), casual aesthetics (comfort over elegance, opposite of Senchado's refined formality). Nearly indestructiblemodern mugs rarely break at handle attachment (usually body cracks first).

The material science: handle strength depends on attachment method. Porcelain/bone china (traditional): Handle and cup body made separately, joined while clay still wet (\"greenware\" stage), fired as single piece. Joint is weakest point (different shrinkage rates, stress concentration), breaks under impact/thermal shock. Stoneware/ceramic (modern mugs): Thicker walls, coarser clay, often extruded handles (pulled from cup body while wet, continuous clay structureno joint). Stronger, but heavier and less elegant. Alternative materials: Metal handles on ceramic cups (riveted/boltedseparable for dishwashing), silicone sleeves (removable insulation), no-handle insulated walls (double-wall vacuum construction, handle unnecessary).

| Handle Material | Thermal Conductivity | Durability | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Porcelain (traditional teacup) | Medium (1-3 W/mK)stays cooler than metal, but not insulating | Fragile (chips/cracks easily, thin attachment points) | Formal tea service, delicate china, display/collection |

| Stoneware/ceramic (modern mug) | Low (0.5-1 W/mK)good insulation, thick walls retain less heat | Very durable (thick construction, strong joints, impact-resistant) | Daily use, dishwasher/microwave, casual drinking |

| Metal (steel/brass, riveted to cup) | Very high (50-400 W/mK)conducts heat rapidly, gets very hot | Extremely durable (won't break, may loosen rivets over time) | Camping/outdoor enamel mugs, industrial settings, vintage aesthetic |

| Glass (borosilicate, fused to cup) | Medium-low (~1 W/mK)similar to porcelain but more uniform | Moderate (thermal-shock resistant, but brittleshatters on impact) | Modern design, visual aesthetic (transparent tea observation), specialty |

| Silicone sleeve (removable) | Very low (0.2 W/mK)excellent insulation, cool to touch | Durable (flexible, impact-resistant, but degrades over years/UV exposure) | Travel mugs, to-go cups, added to existing handleless cups |

4. Ergonomic Evolution: Comfort vs. Aesthetic

Handle design balances functionality and appearance: Functional priorities: Adequate finger space (adult fingers need ~2-3cm gap minimum), comfortable grip angle (handle tilted 10-15 outward from vertical prevents wrist strain), sufficient strength (support full cup weight + lifting force, ~2-3 static weight as safety margin), heat resistance (handle stays cool enough to hold, <45C surface temperature). Aesthetic priorities: Visual proportion (handle size matches cup sizetiny handle on large cup looks wrong), style consistency (handle curve echoes cup shapeelegant loop for delicate cup, robust D-shape for chunky mug), decorative elements (carved details, gilding, sculptural formsadds beauty/prestige).

The ergonomic failures: Too-small handles: Fingers don't fit (especially men's hands, larger sizes), creates pinching grip (uncomfortable, insecure hold). Common in vintage teacups (designed for smaller 19th-century women's hands), frustrates modern users. Too-far handles: Attached far from cup rim (long leverage arm), creates tipping moment when filled (cup wants to rotate, spill liquid). Physics: torque $ \\tau = F \\times d $, where $ F $ is liquid weight, $ d $ is distance from grip pointlarger $ d $ increases instability. Too-thin handles: Press into fingers (small contact area, high pressure), painful during extended holding. Too-close to cup body: Fingers touch hot cup wall (defeats handle's purpose), especially problematic on large filled cups (liquid level reaches handle attachment zone).

The optimal handle: studies suggest 2.5-3.5cm internal width (fits most adult hands), attached ~60-70% up cup height (balances leverage and clearance), thickness 8-12mm (comfortable contact, structural strength), clearance 12-15mm from cup body (finger space without cup contact). Modern industrial design uses ergonomic modeling (3D scan hand grips, computer simulation of stress distribution, user testing with diverse hand sizes)result is boringly functional handles (work well, rarely break, zero aesthetic flair). Artisan/luxury teacups prioritize beauty (sculptural handles, decorative details, uniqueness), sometimes sacrificing comfort. The market segments: cheap = pure function, mid-range = balanced, luxury = art-first.

Expert Tip: The \"Try Before You Buy\" Handle Test

When purchasing teacups/mugs, test handle comfort: (1) Empty grip: Insert fingers through handledo they fit comfortably without scraping cup body? Can you grip securely without strain? (2) Simulated weight: Fill cup with water (or pick up similar-weight object), hold by handle onlydoes it feel secure, or tippy/awkward? Is handle pressing into fingers painfully? (3) Hot test (in store): Ask to fill with hot water (most tea shops/cafes accommodate this request)does handle stay cool enough to hold comfortably? After 2 minutes (test thermal equilibrium, not just initial cool). (4) Sip simulation: Bring cup to lips while holding handleis wrist angle comfortable, or does it twist awkwardly? An uncomfortable handle ruins tea experience dailyworth 5 minutes testing before committing to purchase.

5. Cultural Signaling: Class, Gender, and the Handle

Teacup handles became status markers in Victorian England (1850-1900): Delicate loop handles signaled wealth/leisure (fragile china = expensive like Da Hong Pao premium teas, requires careful handling = servant-assisted lifestyle at afternoon tea, no manual labor = soft hands can manage delicate grip). "Proper" holding technique (index through loop, middle/ring supporting cup bottom, wrist elegantly bent) became class identifierpracticed through etiquette training similar to Persian tarof rituals, marked "refined" individuals. Large sturdy handles signaled working-class (thick mugs for laborers, builder's tea in indestructible vessels, fist-grip drinking without performance).

The gender dimension: tea service feminized in Western culture (Victorian tea gowns and afternoon tea as women's social space, delicate teacups as feminine objects, handle aesthetics prioritizing beauty over strengthcoded feminine). Men's tea often in mugs (robust, larger, minimal decorationcoded masculine, like Australian billy tea's rugged outdoor culture). This gender-coding persist: women more likely to own/use cup-and-saucer sets (saucer formality associated with feminine entertaining), men default to mugs (casual, functional, no fuss like grandpa style's simplicity). The coding is cultural construct (nothing inherently gendered about handle size, as mate's gender-neutral sharing shows), but shapes product designmanufacturers create "women's teacups" (delicate, floral) vs. "men's mugs" (large, solid colors).

The modern rebellion: gender-neutral tea culture emerging (specialty coffee's influence, artisan tea shops like those serving bubble tea, younger generation rejecting binary categories). Handle design increasingly unisex: focus on functionality (comfortable for all hand sizes), aesthetic diversity (personal expression over gender performance, similar to modern tea tattoo trends), material quality (craft over decoration echoing wabi-sabi values). But traditional tea service maintains old patternsformal afternoon tea still coded feminine, heavily-handled mugs still coded masculine. Cultural lag: objects retain symbolic meanings long after attitudes shift.

6. The Handleless Revival: Modern Design Trends

Contemporary tea culture sees handleless cups returning: Double-wall glass cups: Borosilicate glass with air gap insulation (outer wall stays cool despite hot tea inside), no handle neededthermal engineering obviates handle's original function. Popular in specialty tea shops (visual appealsee tea color, watch leaves unfurl), modern aesthetic (minimalist, architectural). Ceramic travel tumblers: Thick-walled insulated ceramic (5-8mm walls), lid with sip-opening, no handle (both hands grip like coffee tumbler). Influenced by coffee culture (Starbucks tumblers, reusable cup trend), crosses into tea market. Japanese-style yunomi: Traditional handleless teacups marketed to Western audiences, part of \"authentic\" Asian tea experience (matcha popularity, sencha ceremony interest, cultural borrowing).

The design philosophy shift: 1750s added handles to solve heat problem (engineering comfort into Chinese design), 2020s solve heat differently (better materials, thermal insulation like teh tarik's temperature management) and remove handles (returning to minimalist aesthetic of Tang Dynasty bowls). The cycle: simplicity ? complexity (add handles) ? sophistication (advanced materials enable return to simplicity, as seen in Gongfu's renewed popularity). This parallels broader design evolution (early cars had complex controls, modern cars simplified via automation/better engineering)technology enables return to elegant minimalism.

The practical trade-offs: handleless modern cups work well (good insulation, cool exterior), but sacrifice one-handed convenience (need both hands to cradle cup, can't drink while typing/reading easily). Handles enable multitasking (work while drinking, one hand free), handleless forces presence (both hands engaged, must focus on tea moment). The choice reflects values: efficiency vs. mindfulness, convenience vs. ritual. No \"correct\" answerdepends on tea's role in your life (utilitarian caffeine delivery vs. contemplative practice).

7. Handle Repair and Longevity

Broken handle is most common teacup damage: Causes: Impact (knocked against sink, dropped), thermal shock (hot tea into cold cup causes rapid expansion, stress at handle joint), age (clay degradation, glaze crazing allows moisture penetration, weakens attachment), manufacturing defect (poor joint, inadequate firing, weak clay body). Repair options: Food-safe epoxy: Two-part resin (mix and apply to broken surfaces, clamp 24 hours). Creates strong bond (often stronger than original), but visible repair line (aesthetically imperfect). Not microwave-safe (epoxy degrades under microwave radiation). Cost: $5-15 for epoxy, DIY labor. Kintsugi (Japanese gold-repair): Fill cracks with lacquer mixed with gold powder, embraces visible repair (aesthetic philosophydamage is history, not flaw). Beautiful but expensive ($50-200+ professional repair), time-consuming (multiple lacquer layers, weeks to cure). Professional ceramic restoration: Specialist glues crack, color-matches repair, polishes to near-invisible. Expensive ($30-100 per cup), usually for valuable antiques/heirlooms only.

The prevention strategies: Avoid thermal shock: Don't pour boiling water into cold cup (warm cup first with hot tap water, then add tea). Especially critical for porcelain (more thermal shock-sensitive than stoneware). Hand-wash delicate cups: Dishwasher mechanical stress + harsh detergents weaken handle joints over time. Reserve dishwasher for sturdy mugs, hand-wash fine china. Store carefully: Don't stack cups by hooking handles (puts weight on weakest point, promotes cracks). Stack handleless, or hang on hooks (transfers weight to rim, stronger structure). Inspect regularly: Check handle attachment for hairline cracks (early detection allows repair before catastrophic failure, prevents losing favorite cup).

8. Alternative Gripping Methods: Sleeves, Holders, and Zarf

Cultures developed handle-alternatives: Zarf (Arabic/Turkish): Metal holder (often ornately decorated brass/silver) that cup nests into, provides insulated grip. Traditional for Turkish tea (small tulip glasses, too hot to hold directly). Zarf functions like detachable handle (removable for cleaning, reusable across multiple cups). Modern version: Russian podstakannik (glass holder for tea, metal frame with handleSoviet-era tea service icon). Silicone sleeves: Reusable grip-wraps (slide onto cup, provide insulation + non-slip surface). Popular for to-go cups (coffee shop reusables), adaptable to various cup sizes. Environmental benefit: makes handleless cups usable (broader compatibility than handle-specific design). Paper/cardboard sleeves: Disposable insulation (coffee shop standard), prevents burns from paper cups. Less relevant for home tea, but shows persistent need to solve heat-grip problem (handles aren't only solution).

The cultural geography: zarf common in Middle East/North Africa (tea served very hot like Turkish ay, prolonged holding while conversing in Persian gatherings), podstakannik in Russia/Eastern Europe (train travel culture, stable holder for moving vehicles), sleeves in Western coffee culture (influenced tea drinking via Starbucks/cafe trend spreading to Hong Kong milk tea shops). Each solution reflects specific use-case: zarf for hospitality (beautiful object enhances guest experience like Moroccan tea's ornate service), podstakannik for mobility (train drinking, portable holder), sleeves for disposability (single-use culture, convenience). The diversity shows: handle is one answer to heat problem, not the answermultiple valid solutions depending on priorities, from Gongfu's handleless gaiwans to Senchado's refined yunomi.

Expert Tip: The Silicone Sleeve Universal Solution

If you have beautiful handleless cups but find them too hot to hold: buy universal silicone sleeve (stretch-fit design, ~$8-12 for set of 4). These work on: Chinese gaiwans (wrap around body), Japanese yunomi (full-coverage insulation), modern double-wall glasses (extra protection if outer wall still warm), antique teacups (preserve aesthetic, add functionality). Benefits: (1) Preserves cup's original design (no permanent modification), (2) Removable for display/formal service (practical when needed, invisible when not), (3) Dishwasher-safe (easy maintenance), (4) Prevents slipping (textured surface, good for elderly/arthritic hands). This workaround lets you use gorgeous handleless cups comfortably without compromising aesthetics or authenticity. Best of both worlds: beauty + function.

9. The Future of Handles: Smart Cups and Material Innovation

Emerging handle technologies: Thermochromic handles: Temperature-sensitive coating changes color (warns if too hot to hold safelyvisual feedback before touching), similar to thermochromic tea pets that change appearance. Novelty currently (kids' cups, gimmick mugs), but practical application for elderly/vision-impaired (tactile heat sensing may be impaired, color warning helpful for noon chai's scalding temperatures). Phase-change material handles: Embedded PCM absorbs heat (melts/solidifies at specific temperature, buffer against thermal spikes similar to teh tarik's cooling management). Used in some travel mugs (keeps handle cool while contents stay hot), could migrate to teacups. Smart cup handles: Embedded sensors (temperature monitoring, liquid level detection, drinking frequency tracking). IoT integration (sync with health apps, "stay hydrated" reminders, caffeine consumption logs from grandpa style's all-day sipping). Currently niche/expensive, may become mainstream as sensor prices drop.

The material frontiers: Aerogel-insulated handles: Ultra-low thermal conductivity (0.015 W/mK, best insulation available), incredibly light, extremely expensive. Potential for luxury teacups (perfect thermal isolation, featherweight design). 3D-printed custom handles: Scan user's hand, print ergonomically perfect handle (fits your exact grip), attach to handleless cup body. Customization-on-demand (every cup optimized for owner's hand size/shape). Self-healing ceramics: Experimental materials that repair microcracks (heat-activated chemical reactions seal damage), could eliminate broken-handle problem. Lab-stage currently, commercialization 10-20 years away.

The philosophical question: as technology solves handle's functional problems (thermal insulation, ergonomics, durability), does handle become purely aesthetic (decorative element, not functional necessity)? Or will handles persist as cultural signifier (\"proper\" teacups have handles, regardless of technical need)? The precedent: many design elements outlive their function (buttons on suit sleeves, stitching on car dashboardsvestigial details retained for appearance). Handles may follow this path: future cups don't need handles (perfect insulation, ideal materials), but keep them anyway (tradition, beauty, \"tea-ness\"). Or handles disappear entirely (minimalist aesthetic wins, function follows form). The next 50 years will tell which path prevailsengineering triumph vs. cultural inertia. Both are powerful forces. The humble handle's fate hangs in balance.

Comments