The Chemistry of "Good Sour": Organic Acids

To understand sourness, we must look at the organic chemistry of the leaf. The tea plant (Camellia sinensis) naturally produces several organic acids as part of its metabolic cycle (The Krebs Cycle). These acids are essential for the plant's energy production and defense mechanisms.

In high-quality teas, these acids are preserved and extracted into the liquor, providing "Briskness" or "Vibrancy." Without them, tea would taste flat and heavy.

1. Citric Acid

Found in trace amounts in tea leaves, but significantly higher in teas grown in mineral-rich soils. It provides a sharp, lemon-like tartness that makes the mouth water. This is a desirable trait in green teas and some high-mountain oolongs.

2. Malic Acid

Often associated with apples, Malic acid provides a smooth, lingering tartness. It is particularly prominent in Taiwanese Oolongs (like Oriental Beauty) and young Raw Pu-erh. It interacts with the sweetness of the tea (Glycosides) to create a "Sweet-Sour" sensation known in Chinese as Hui Gan (Returning Sweetness).

3. Succinic Acid

This acid delivers a savory, umami-like sourness. It is crucial in Japanese Green Teas like Gyokuro. When combined with amino acids (Theanine), it creates the broth-like richness that defines the style. Read more about Umami and Amino Acids here.

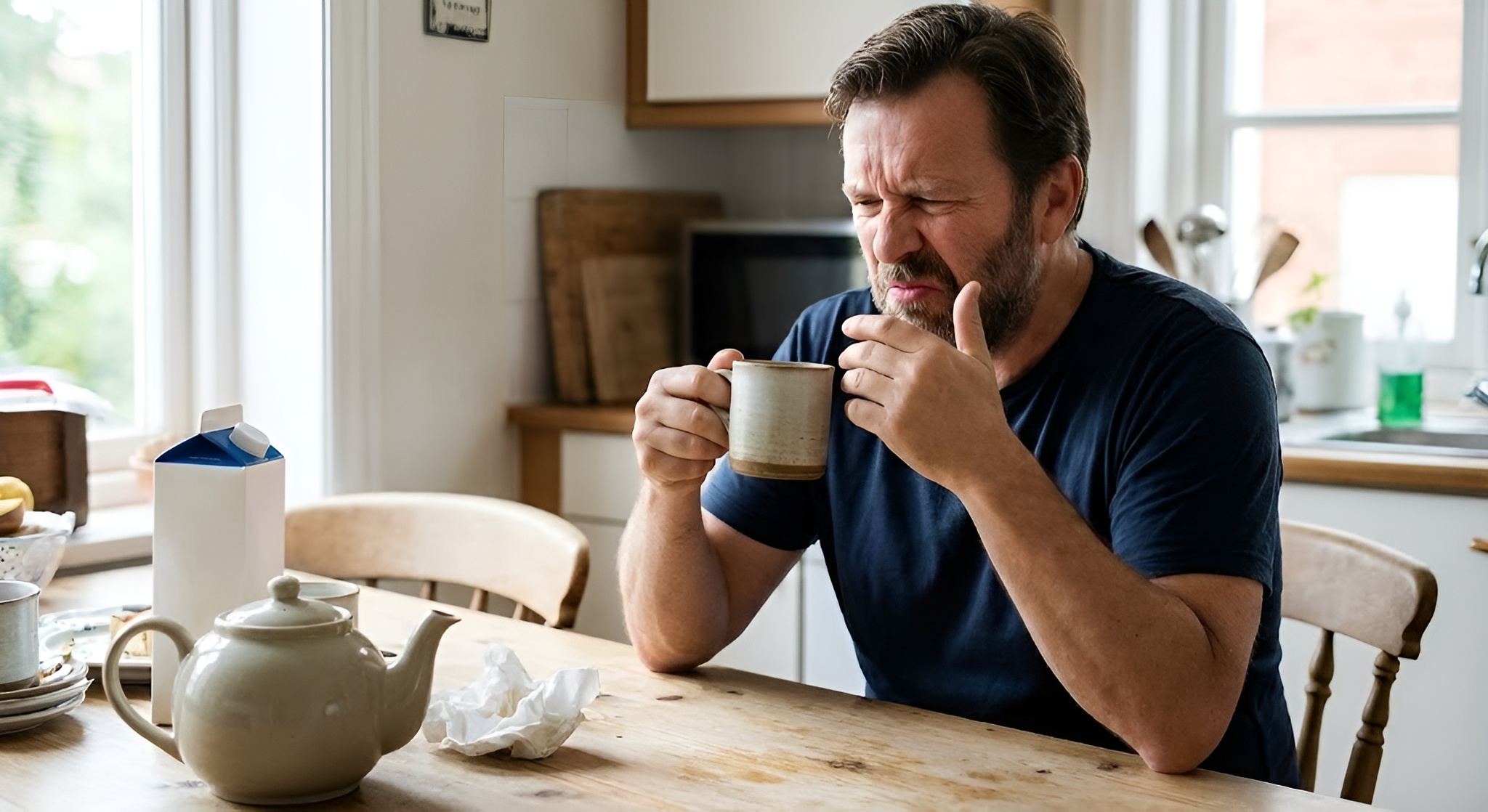

The Saliva Test

How do you tell Good Sour from Bad Sour? Pay attention to your saliva. Good Acidity (Natural Organic Acids) makes you salivate at the sides of your tongue (like biting a green apple); it feels refreshing and cleansing. Bad Sourness (Spoilage) makes your mouth feel dry, sticky, or curdled. Your body naturally wants to reject spoiled food, so trust your instinct. If it feels "wrong," it probably is.

Varieties with Natural Acidity

Certain teas are famous for their acidity. If you taste sourness in these, it is likely a sign of quality, not spoilage.

Darjeeling First Flush

Often called the "Champagne of Teas," spring-harvest Darjeeling is essentially a raw, unoxidized black tea. It is rich in Theaflavins and Catechins, which can present as a crisp, tart note reminiscent of green grapes, gooseberries, or unripe peaches. This is a prized characteristic. Read our guide to First Flush profiles.

Young Sheng (Raw) Pu-erh

Raw Pu-erh that is less than 5 years old is chemically potent. It contains active enzymes and high levels of aggressive compounds. A young Sheng often has a distinct "sour plum" (Suan) note. This is considered a positive attribute if it quickly transforms into sweetness. If the sourness lingers and feels "locked" in the throat, creating a puckering sensation that won't go away, that is a flaw or a sign of poor storage. Learn the difference between Sheng and Shou here.

The "Bad Sour": Microbiology of Spoilage

When sourness is sharp, vinegary, or accompanied by a funky smell, it is usually caused by microbial activity. Tea leaves are dried to a water content of 3-5% to prevent bacterial growth. If moisture levels rise, dormant microbes wake up and start eating the tea.

1. Bacterial Souring (The "Sour Rot")

If dried tea gets wet (humidity above 60%) or is touched with a wet spoon, bacteria like Lactobacillus or Acetobacter can colonize the leaves. These bacteria consume the sugars in the tea and excrete Acetic Acid (Vinegar) or Lactic Acid (Sour Milk).

- The Smell: Sour milk, vinegar, wet dog, or old gym socks.

- The Visuals: Often invisible. Unlike mold, bacteria do not always produce visible fuzz.

- The Danger: While some bacteria are harmless, others can produce toxins that are heat-stable. You cannot "boil off" the toxins produced by spoilage bacteria. If your tea smells like vinegar, throw it away.

2. The "Wet Storage" Debate in Pu-erh

In the world of Pu-erh, things get complicated. "Traditional Hong Kong Storage" intentionally exposes tea to high humidity to speed up aging. This can create a temporary sourness known as the "Wodui" taste. However, there is a fine line between "controlled aging" and "rotting."

If a Ripe (Shou) Pu-erh tastes distinctly sour and fishy, it often means the fermentation pile got too hot or lacked oxygen (Anaerobic fermentation), leading to the growth of undesirable bacteria. This is considered a fault. Read our full guide on why Pu-erh tastes fishy.

Water Activity (Aw)

In food science, spoilage is determined by "Water Activity" (Aw), not just moisture content. Tea is safe below 0.6 Aw. If you store tea in a humid environment (like next to a dishwasher or kettle), the leaves absorb moisture from the air, raising the Aw above 0.6 and allowing bacteria to multiply. Always store tea in airtight tins in a cool, dry place. See our definitive Tea Storage Guide.

Brewing Errors: When You are the Problem

Sometimes the tea is fine, but the brewing parameters have chemically altered the pH balance of the cup.

Over-Steeping & Tannins

Leaving the leaves in too long extracts excessive Tannins (Polyphenols). While tannins are primarily bitter and astringent, an overdose of certain tannins (like Theogallin and gallic acid) can register as sour on the sides of the tongue. This is especially true for broken-leaf teas or tea bags (dust grade) which infuse rapidly. The sourness here is usually accompanied by a mouth-drying sensation. Understand tea bag grades here.

Thermal Degradation (The Thermos Effect)

Have you ever put hot tea in a thermos and found it tasted sour 4 hours later? This is Thermal Degradation. Keeping tea at high heat (above 80°C) for prolonged periods causes the chemical compounds in the liquor to break down (hydrolysis). Esters (flavor compounds) degrade into acids, and complex sugars caramelize and then burn. This results in a flat, metallic, and distinctly sour taste. Tea is best drunk fresh. If you need it for travel, cool it down rapidly first to stop the chemical reactions.

The Hidden Variable: Water Chemistry

Tea is 99% water. The chemistry of your water source can drastically change the flavor profile and pH of your brew.

1. The Buffer Effect (Alkalinity)

Tap water usually contains minerals like Calcium and Magnesium (Bicarbonates). These minerals act as a "Buffer," neutralizing the natural acids in the tea. This results in a rounder, smoother, but sometimes flatter taste.

2. The Reverse Osmosis (RO) Problem

If you use Reverse Osmosis or distilled water, you have removed all the minerals. This water has zero buffering capacity and is often slightly acidic (pH 5-6) due to absorbing CO2 from the air. When you brew tea with this "empty" water, there is nothing to neutralize the natural organic acids in the leaf. The result is a cup that tastes sharp, thin, and aggressively sour. If your tea consistently tastes sour regardless of the brand, try switching to a neutral spring water (pH 7) or adding a pinch of baking soda to your RO water. Read our deep dive on Water Quality for Tea.

Troubleshooting Guide

| Symptom | Likely Cause | Fix |

|---|---|---|

| Sour + Clean/Fruity | Natural Acidity (Good) | Enjoy it! It's a sign of quality in Darjeeling/Sheng. |

| Sour + Vinegar Smell | Bacterial Spoilage | Discard. The tea has fermented/spoiled due to moisture. |

| Sour + Fishy | Bad Fermentation (Pu-erh) | Airing it out might help, but likely low quality processing. |

| Sour + Dry/Astringent | Over-steeping / Too Hot | Reduce temp and time. Use more water. |

| Sour + Metallic | Thermos / Water pH | Drink fresh or switch water source. |

Comments